|

Food delivery apps have made us a bold promise: order any dish, from nearly any restaurant, at any time.

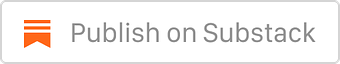

But there is one big problem with their business: the high price. While a single urbanite making a six-figure salary might be able to afford to pay over $20 per person for dinner every night, the majority of the people in the US can’t justify that kind of spend.

|

(Source: 2PM, December 2019)

However, the consumer trend to order delivery more often is undeniable. It’s been especially prominent in the past few months, due to coronavirus shelter-in-place orders. More people are ordering food through apps than ever before. And many smart people believe that the kitchens in our homes will soon become antiquated, for the same reasons we don’t sew our own clothes anymore. Plus, even after life goes back to normal, it’ll probably be a while before people feel comfortable crowding into restaurants and bars again.

This leads to an interesting problem: there’s something people want (food delivery), but there’s a big barrier for them to purchase it (price).

The price is high not because the restaurants or delivery companies are hoarding profits, but because there are high fixed costs with food delivery. The courier requires a minimum wage. The ingredients can only be so cheap. There just aren’t a ton of things throughout the food delivery value chain that restaurants can innovate on without significant technological advances.

But one way they can innovate is by rearranging the existing component. In particular, by renting space in areas with less foot traffic, businesses can lower one of their biggest expenses: real estate costs.

And if people are ordering food through an app and having it delivered to them, what’s the point of paying for premium retail? What’s the point of employing extra staff to make customers feel comfortable when they enter the restaurant?

This is the problem cloud kitchens are trying to solve. And lots of ambitious entrepreneurs (including ex-Uber CEO Travis Kalanick) believe this is one of the next big trends in food and logistics. And while “cloud kitchens” have only recently become a household term, the concept isn’t completely new.

In fact, Domino’s Pizza has been reaping the benefits of cloud kitchens for years.

|

Think about the similarities between cloud kitchens and Domino’s:

Stores have small / no dining space and are optimized for delivery

Location of real estate is focused on the best routes, not the best foot traffic

Food product travels well and can feed a lot of people for cheap

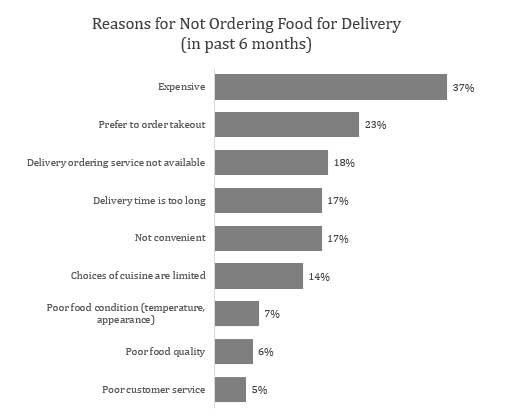

And while Domino’s is certainly benefiting from the rise of delivery (especially during COVID-19), one of the main reasons they did so well over the past decade has been the alignment of their business and their business model.

Strategic Investments

In 2009, Domino’s made a number of decisions to align their strategy to their business model.

First, they completely overhauled their product. It went from tasting like cardboard to tasting like, well, real pizza. And they even ran an ad campaign where they owned up to their previously bland product, and described how they improved it. It also helped that the product category (pizza) was extremely well-suited to delivery because it’s cheap: a single pizza can feed a family of four.

Then, they invested in technology. They were the first to both offer mobile ordering and to build a Pizza Tracker on their website, a concept that delivery startups have since copied. This not only helped them with ordering and logistics (stores and drivers utilize software as well) but also built a digital brand directly with consumers.

This brand advantage is especially important during quarantine, where the customer journey almost always begins online. A lot of other big takeout chains rely on aggregators like DoorDash or Uber Eats and are forced to suffer the high take rates that come with them. So now we're even starting to see a migration of restaurants building their own apps, similar to what Domino’s did a decade ago.

Finally, Domino’s stores are optimized for delivery and takeout, not in-store eating. In contrast, competitors have followed more traditional models: Pizza Hut has a dine-in focused model and mom & pop pizza shops don’t have the technology or delivery infrastructure (although Slice is trying to change that).

While all of these decisions prepared Domino’s for the cloud kitchen era, one of the biggest drivers of investor returns was their franchise business model. It can’t be understated how closely their strategic decisions played into becoming one of the most successful franchises in history.

The Benefits of a Franchise Model

Franchise businesses can be incredible. Here’s why.

Usually when a business wants to grow, they need to use existing profits or raise new capital to fund that growth. However, a franchise business is the opposite. The franchisor can add new locations, but doesn’t need to front the capital themselves. Instead, they can source the capital required to open new locations through their franchisees.

In return for the brand awareness, trade secrets and operating best practices, franchisees pay monthly commissions to the franchisor. For the parent company, it becomes a cost-free royalty, a perpetual stream of cash. And if a franchisor is performing well, they can actually distribute cash back to shareholders even as they grow, instead of needing cash to fund expansion.

So if franchises are so great, why doesn’t everyone run one? The short answer is because not every business is built to entrust franchisees with quality control.

Consider a company like Starbucks. One big reason people go to Starbucks is to spend a few hours working in a comfortable place, or to enjoy their coffee with a friend. Additionally, many Starbucks customers decide to purchase a coffee because they walk past a store. They don’t have as much delivery either: the low price of a coffee (~$5) means that the delivery costs up to 50% of the total order value. Much too high for most people.

These business characteristics make it harder for Starbucks to adopt a franchise model. The consumer value proposition is reliant on in-person experience: sitting in a comfortable lobby while enjoying the music, chatter and aura of the environment. And that’s much harder to scale through a network of franchisees. Starbucks would be relying on independent operators to accurately replicate that unique environment, which is hard to do.

And that is one reason why none of the Starbucks stores are franchised. One hundred percent of them are owned by the company.

Contrast this with Domino’s. Pizza is a cheap and standard product that is easy to make. Dough, sauce, toppings, oven -- that’s it. Simple and repeatable.

Additionally, Domino’s invested in technology and built an independent, digital-first brand before anyone else. When you think, I want to order pizza online, do you picture the Domino’s pizza tracker? I do. It’s not as tied to a particular store as it is to the Domino’s brand and online portal (which is controlled by Domino’s corporate employees).

And finally, their stores are optimized for delivery instead of dining in. Their store locations are selected by optimizing for the best delivery routes, not the most foot traffic. And even beyond that, Pizza is commonly ordered in groups. This increases the average order value, making the delivery expense small as a percent of the total value.

All these decisions funnel quality control to the parent company and make it much easier to hand off a store to a franchisee. When more of the consumer experience is provided by the parent company, the only thing operators need to have is money and grit.

So while both Starbucks and Domino’s needed tasty food and beverages to grow, Domino’s structured its business to be much more suited for the franchise model. And it paid off.

“CapEx-Lite” Growth and Cash Distributions

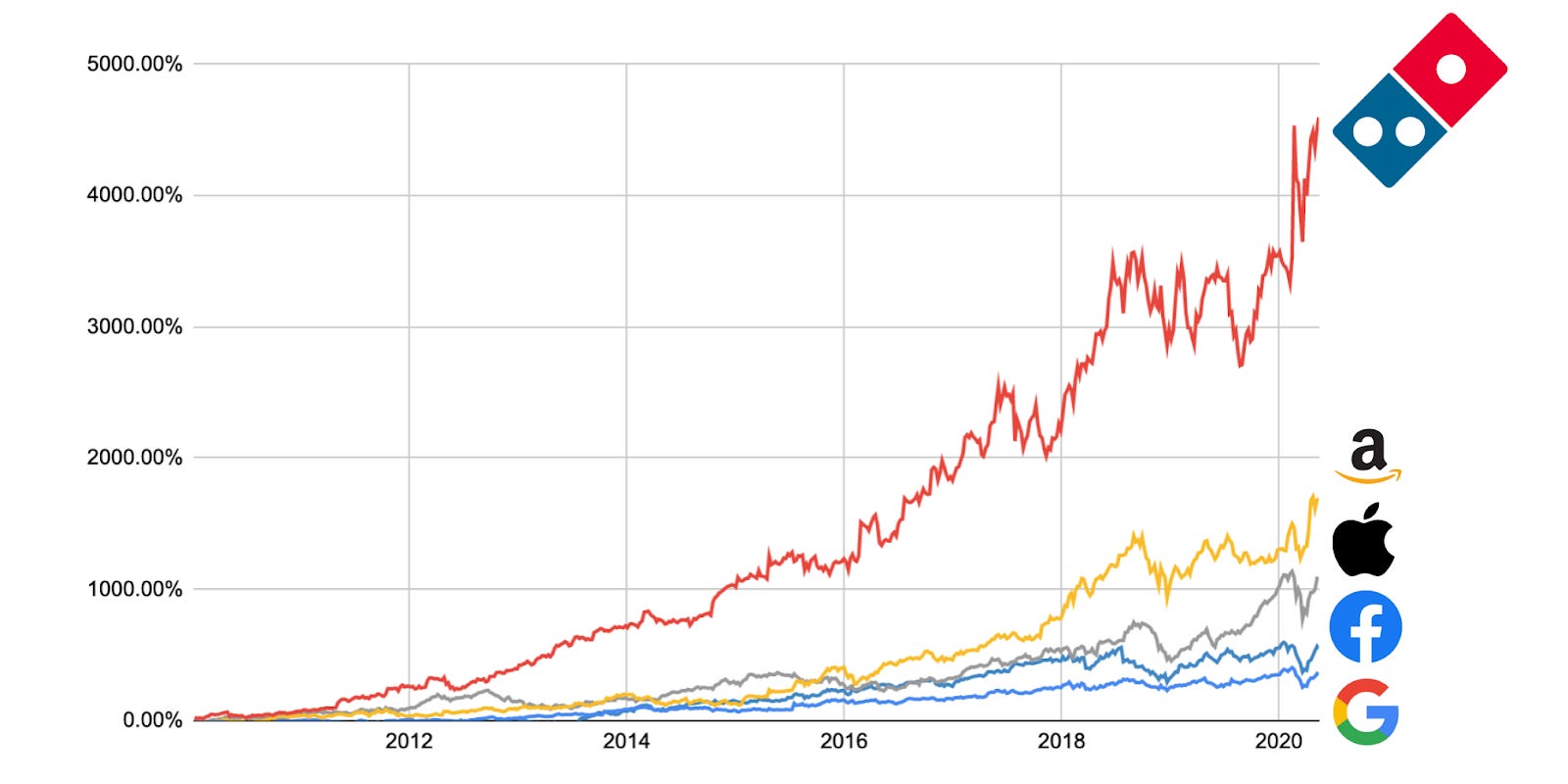

From 2012 to 2019, Domino’s not only grew revenue by 12% per year, but also grew net earnings by 20% per year and returned almost $4.5 billion in cash to equity holders through dividends and repurchases. How did they do it?

Domino’s opened lots of restaurants through this time period. But the most important factor is that they didn’t need to provide the cash up front to build the stores. Instead, the operators did. According to their 2019 10-K, capital expenditures accounted for less than 1% of revenue for the international segment (the only segment that is 100% franchised).

This allowed Domino’s to grow their high-margin franchise commissions (3.5% - 5.5% on every franchise) without bleeding very much cash.

Then — because of the capital efficiency of franchises, consistency of growing revenue, and strong asset base — they were able to maintain a high debt level (4.5x - 5.0x EBITDA). And with interest rates at all-time lows, their interest expense didn’t cripple their operations in the slightest.

They ended up issuing just under $6.5 billion in debt over that period, and while a decent chunk of it went to refinance old notes, another big chunk went to equity holders through special dividends and buybacks.

The result is quite unique: a company growing earnings 20% per year while still distributing loads of cash to shareholders. It’s excellent work.

|

(Source: company filings.)

Domino’s: The Ideal Cloud Kitchen

It turns out that several of the things that made Domino’s a great franchise model and equity investment also made them perfectly situated in a quarantine, delivery-first world.

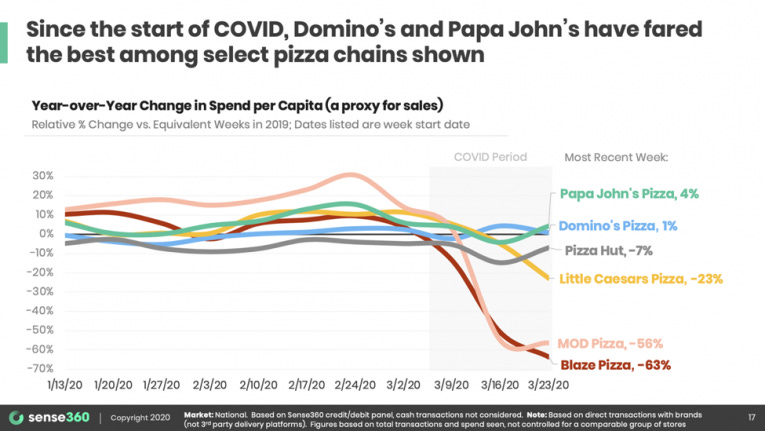

Domino’s and Papa John’s are performing a lot better than the chains that are optimized for dine-in or personalized orders. They are the pizza chains that are most optimized for delivery and large orders, which is what consumers want right now.

|

(Source: Sense360, via QSR Magazine)

And while Domino’s same-store sales only rose 1.6% in the first quarter, in the four-week period that followed (March 23 - April 19), same-store sales rose 7.1%, with reports that digital orders accounted for 80% of sales in one of those weeks. This is a much better fate than a lot of restaurants which have had to shut down completely.

All this to say that Domino’s is the platonic ideal of future cloud kitchens. The company’s foresight to optimize for delivery, place stores in low-cost and route-optimized retail locations, and build a digital brand and app that really works is now paying off.

Even before the coronavirus, home delivery was a growing trend that the biggest names in startups and food delivery have been trying to crack and turn into a venture-scale business.

It just turns out that the pizza guys got there first.

Enjoy this?

Press the “like” button, so we know to do more like it in the future!

Also, if you want to understand the food delivery value chain in more detail, we’re publishing a piece next week that will interpret Domino’s success using the “Finding Power” framework we published recently, which distills great ideas from Clay Christensen.

Here’s the short version: every industry is really a “chain” of activities that fit together to transform raw resources into completed products. Some activities tend to accumulate way more power and profits than others, though, for the people who perform them.

How do you know which activities will yield the most power? That’s the exact question Clay Christensen’s theory was designed to help you answer.

Want to get Superorganizers?

If words like “Roam,” “Zettelkasten,” and “Second Brain” mean anything to you, I think you’ll love Superorganizers. It’s a newsletter on productivity that features interviews with the world’s most creative people, and in-depth explainers to help you do your best work.

Normally a subscription costs $15/mo, but I’ve teamed up with Dan Shipper to offer bundled access to the premium editions of both Divinations and Superorganizers for just $20/mo. That’s a pretty good deal compared to the $28/mo they’d cost to buy separately!

Want the bundle but can’t afford it for any reason? Email me and we’ll work something out!