The reason why this toy is still sealed is because the poor kid couldn’t figure out how to open it up. (via eBay)

How we got blister packaging, and why it’s so frustrating to use

Throughout my childhood, I have lots of memories of getting gifts—often of the handheld, gadgety variety—and not being able to use them right away, because I couldn’t open up the package.

It was like a prison of plastic that surrounded the Tiger handheld game I just received—a well-formed blister of flexible, but thick plastic that prevented me from playing Aladdin, or opening up that pack of batteries I needed to get my Game Boy going.

In many ways, these products are prime candidates for blister packaging. They’re fairly small in size; they’re not cheap, but not expensive, either; at their heart, they are impulse buys.

Blister packaging, which relies on molded plastic, was not at its heart an anti-consumer mechanism. In fact, one of its primary use cases was specifically intended to help consumers. In the 1960s, blister packs became a key element of delivering medicine to consumers—with oral contraceptives, which needed to be taken on a timed cycle, one of the first successful products to use foil-backed blister packs.

These pharmaceutical packages are fairly common today, and make it easier to properly measure dosage.

But how did packaging companies shape the plastic in such a way that they could create the blister? In many ways, it comes down to the unique properties of plastic, which vary based on type.

Pharmaceutical blister packs are close cousins of the kind that annoy people in retail settings. (Efraimstochter/Pixabay)

Generally, plastics are susceptible to two types of phenomena, depending on the variant: Thermosetting, in which plastic becomes stronger when it gets hotter; and thermoforming, in which plastic becomes more malleable with heat.

Thermoset plastics were the most popular type around when plastic first went mainstream; bakelite, a common early type of plastic that has become collectible in recent years, is a thermoset, and it has tended to be used in heat-resistant settings.

But thanks to heat, thermoformed plastics (of which PVC is a prominent example) tend to be much more flexible and moldable, which makes them well-suited for packaging. It was these qualities that made them useful for “blister”-style packaging, which refers to the fact that there’s an object inside of the molded plastic lump, just as there’s something inside the blisters you get when you take a 10-mile walk.

Add a little bit of heat in the right spot and you can mold a sheet of plastic any which way—and ensure that plastic perfectly matches the shape of whatever piece of junk you’re trying to sell.

It’s in this spirit that new forms of packaging emerged that took advantage of these properties—first, medical packaging in the 1960s, and then starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s, blister or clamshell packaging.

Clamshell packaging in particular is an interesting case. It’s the kind that people think of when they think of packaging that turns into a strugglefest. Commonly, an inventor named Thomas Jake Lunsford gets the credit for this type of packaging, which involves putting the product and any manuals or promotional materials in the middle of two plastic halves. Previously, most packaging of this nature had a cardboard back half which was easier to remove, but effectively allowed for the destruction of the package just to use it.

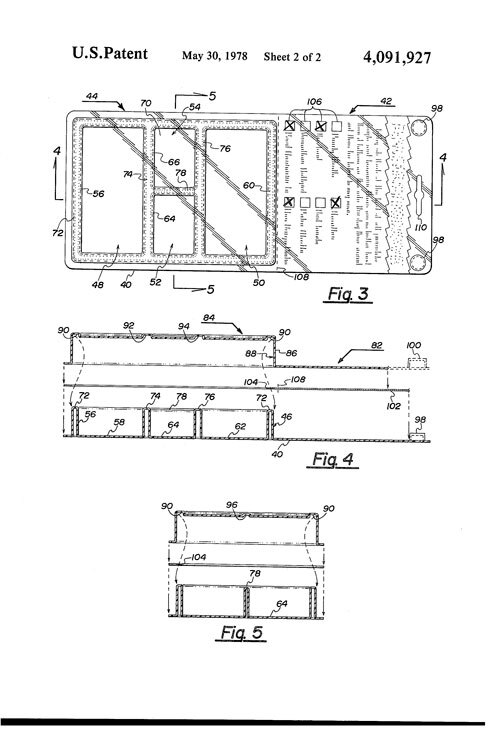

This clamshell packaging patent is not as annoying as the one used on the Tiger electronics toy above. (Google Patents)

I’m not totally convinced he deserves the blame, though, because if you look at his invention, it’s fairly innocuous compared to the clamped-down experiences that most people associate with wrap rage, and most importantly, Lunsford says in his patent application that his design is intended to be reusable—something most clamshell packs assuredly are not.

It may be a case where Lunsford built something with good intentions only to see later inventors develop those goods with bad intentions.