(Mr Cup/Fabien Barra/Unsplash)

The fateful decision that probably made typography on graphical user interfaces suck a lot less

Over its nearly 25-year history, lasting from 1981 to 2005, the Seybold Desktop Publishing Conference, also known as Seybold Seminars, don’t have the computer-history pedigree of massive tradeshows like Comdex or CES. It was a fairly narrow, niche affair, focused on the art of print design and the way that computers could push it forward.

But there was a time that technology giants took this event seriously, because of the outsize role that desktop publishing played in the computer industry at the time. In 1989, it was a niche that mattered.

And in 1989, it was where a schism between three brand-name technology companies appeared.

Tensions were high, as highlighted by what the CEO of one of those companies, Adobe cofounder John Warnock, reportedly said during a speech: “That’s the biggest bunch of garbage and mumbo jumbo. … What these people are selling you is snake oil!”

Who were the snake oil slingers? Why, Apple and Microsoft, of course. The two dominant operating system providers had announced a collaboration at the even around a new type of outline-based typography technology, TrueType. And according to Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders, Warnock was upset.

He had reason to be, as the collaboration between Apple and Microsoft—Apple was offering a free, open license of a technology it developed to Microsoft in hopes that it would use it for its next operating system—threatened his company. Adobe, before it became known for its popular (and arguably too dominant) Creative Suite, had built its name upon a programming language for the electronic publishing called PostScript.

This technology was fundamental to the desktop publishing industry, allowing for accurate printing of graphics, offering a basis for laying out vector graphics, including typography, that would look the same on screen as they did on a printer—a key element of “what you see is what you get” (WYSIWYG) publishing.

But it had some weaknesses: The type on a screen was not anti-aliased, as it was primarily intended as a rendering language for printers. (TrueType on the other hand, was built with both screens and printers in mind.)

But beyond technical differences, there were also ownership considerations. Adobe’s licensing was strictly proprietary prior to the TrueType announcement, meaning that it threatened to be a bottleneck for future graphical innovation on computers. It was a good place to be when your market was just desktop publishers, but the problem was that the market was expanding at the time and an “open” approach to standardization was simply better for everyone.

Still, it could have meant bad news for Adobe. As Inside the Publishing Revolution: The Adobe Story put it, “It was an emotional moment for all of Adobe, not just Warnock. The company was under attack, and one of its attackers was a former ally.”

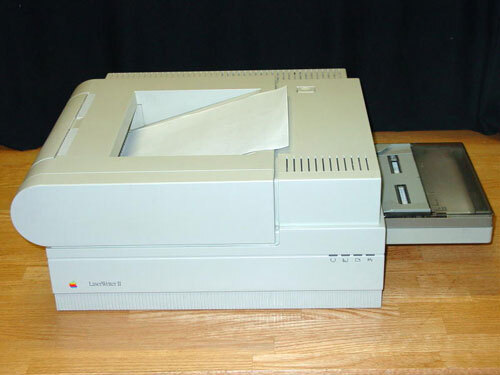

The Apple LaserWriter II. Adobe and Apple had a close relationship thanks in part to the LaserWriter series of printers, which used PostScript. (Wikimedia Commons)

That ally was Apple, which had worked closely with Adobe on its LaserWriter printers and whose operating system had proved fundamental to Adobe’s legacy. Suddenly, the company that helped build Adobe looked like it was about to kill it—and that’s certainly how Warnock took it.

But it’s worth keeping in mind the innovation itself before pulling out the pitchforks. TrueType, even as it may have frustrated Adobe to no end, was ultimately a good thing for the technology industry, because even with its technical deficiencies compared to PostScript, it was good enough for many. And there were some advantages, too: PostScript was initially designed to allow for very general rendering of vector-style fonts, with the more sophisticated rendering happening with the printer. Now, Apple and Microsoft had embraced a technology that allowed for high-quality screen displays along with having decent printing capabilities. They were two different approaches to solving a related, but not the same, problem.

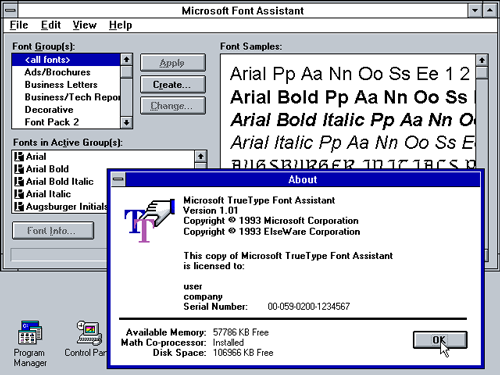

An example of TrueType in Windows 3.1. Despite its close association with Windows, Apple actually developed the TrueType technology, not Microsoft—though Microsoft did develop many of the fonts that became famous as TrueType fonts. (via WinWorldPC)

And TrueType’s uptake with Windows, starting with Windows 3.1 solved some big problems. Example: Early limitations in memory and specification meant that initial laser printers, which relied on fonts using PostScript, didn’t have the level of font support that modern printers do. In fact, some manufacturers turned that limitation into a business model.

Jim Hall, a longtime manager at HP’s Idaho facility who headed up the development of the earliest LaserJet printers, wrote in a history of the printer line that HP had initially treated fonts in the same way it treats printer cartridges today:

Fonts were a challenge for the first LaserJets. Semiconductor memory was very expensive and customer font requirements very fragmented. For those reasons, we elected to offer a limited number of “built-in” fonts and supply the rest in optional font cartridges. This satisfied mainstream users, kept the printer cost low and still gave customers a way to satisfy their special font requirements. Font cartridges (and fonts) became another responsibility for [HP employee] Janet Buschert. Through her efforts, this soon became a major business in its own right with more than 25 different cartridges at prices ranging from $150 to $330 each. It remained a good business for us into the early ’90s when Microsoft started bundling fonts with their Windows operating system.

It turns out that, despite Microsoft’s font-bundling removing a revenue source for HP, the company actually saw it as a good thing, per Hall.

“This was a huge advantage to HP in that it mostly solved our font problem and made WYSIWYG much better by ensuring matching screen and printer fonts,” he said.

The battle between Adobe and Microsoft pushed Adobe to innovate, and it created Adobe Type Manager to allow users to have nice-looking anti-aliased fonts on screen that also had all of the printing advantages of PostScript. And while PostScript certainly couldn’t win over first-time home computer users with a paid font rendering tool, it held onto its higher-end business users, which still purchased Adobe Type Manager for use with Adobe’s Type 1 fonts.

In practice, the schism between Adobe and Microsoft was a case of a market self-selecting itself. It allowed for high-quality typography to go mainstream—driven by Microsoft’s use of TrueType in Windows, which was basically a value add to the operating system—while still leaving room for Adobe in the market, as most desktop publishing firms used Adobe Type Manager, because their focus remained on the printed page. That decision might have looked like a threat to Adobe, but in reality, there was still room for everyone to thrive.

By the late ’90s, the cold war ended in a truce: Adobe and Microsoft came to collaborate on a successor typography technology called OpenType, which effectively merged support between TrueType and Type 1 fonts.

While not having anywhere near the profile of later conflicts, the typography conflict between Adobe, Apple, and Microsoft pushed things forward in much the same way as the conflict over putting Flash on the iPhone.