How CompuServe convinced the country’s largest newspapers to put their stories on its service

The Columbus Dispatch’s early experiments with CompuServe were no accident.

They came about in part to some savvy discussions on the part of CompuServe’s cofounder and early CEO, Jeff Wilkins.

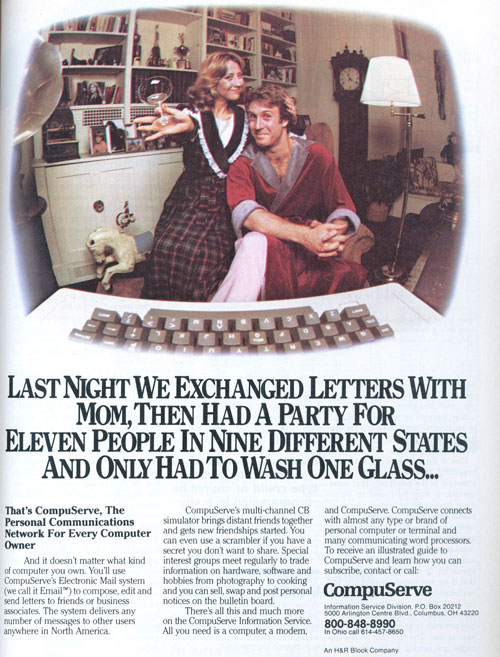

The firm, which got its start in 1969 as a computer time-sharing firm targeted at large companies, slowly evolved into a consumer-targeted service that offered different kinds of online software to end users. One of those software ideas was searchable news, something that Wilkins championed as a larger concept.

In an interview for the podcast Conquering Columbus Wilkins noted that the firm wanted to get the Associated Press, which had previously only been available to the public through dead trees, onto its service. Wilkins first approached the Dispatch, talking them into giving the online service a test feed to try things out.

Eventually, Wilkins reached out to the Associated Press directly, traveling to New York to show the concept to AP officials, who then brought the idea in front of the board of the American Newspaper Publishers Association (ANPA). The board, which got a gander of the concept at a meeting in Hawaii, proved so intrigued by what they were shown that members of the board, including Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham and New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger, decided to made a special trip to Columbus to meet with CompuServe in person.

Wilkins, who had initially wanted to pay for a direct AP feed, managed to flip the script: He asked for the association to let him have access to the feeds of 10 large papers for a test, in exchange for $250,000 in free advertising from each paper. ANPA not only agreed to that deal, but said it would be willing to get each of its member papers on board as part of an ongoing test of the service—one that, in the end, would last approximately two years.

“So, we ended up with every big newspaper in the United States,” he said in the podcast.

It may have been the greatest negotiation in business history. Put in a room with the most powerful publishers in the newspaper industry, CompuServe’s executives managed to convince the AP’s members to give away their copy for free—all by portraying it as an experiment.

“Oh, it was beyond our wildest dreams, all I could do to stop from keep from jumping up and down,” he added.

Alas, the idea proved more successful in theory than in execution. According to the 2008 book, On the Way to the Web: The Secret History of the Internet and Its Founders, the experiment ended with something of a thud, with just 10 percent of CompuServe’s users regularly using the platform and outside beta testers complaining about the lack of photos. (And those users weren’t even paying $5 an hour!)

Additionally, questions quickly arose about whether services like CompuServe would endanger the golden goose:

The test brought out quite a bit of data about online demographics and reading habits. Most users were males in their thirties, with decent incomes. They logged on for email, news, shopping, gaming, banking, and so on. But newspaper publishers weren’t as interested in these things as they were in assurances that online services were no threat to newspapers and their advertising base. They got that assurance from AP spokesman Larry Blasko, who told them, “There is no danger to the American newspaper industry from electronic delivery of information to the home.”

Newspapers had survived radio. They had survived television. According to ANPA, they would survive computer networks.

According to the passage of time and highlighted by the demise of ad revenue at many print newspapers, that may have been a bad bet.