Co-authored by Neer Sharma and Nathan Baschez

|

Variety: When this all happened, you were still in high school and living in your hometown. How has your life changed?

Charli D’Amelio: At first, it was really uncomfortable because when TikTok started, it was kind of like, “Oh, you’re on TikTok? That’s weird.” So I wouldn’t tell people.

1

Facebook is at it again.

A serious competitor has emerged, and so, like clockwork, they put a copy inside Instagram.

This gambit raises all sorts of strategy questions, such as:

Why do they keep doing this?

Will it work?

What happens if it doesn’t?

There’s a popular narrative that says Mark Zuckerberg is a ruthless Machiavellian who likes to destroy his competition for fun. It could be true. But, to be fair, social networking is one of the largest and least understood industries in human history. Perhaps a pinch of paranoia is prudent!

The problem is simple: people only have so much time in the day to scroll through feeds and create content. And when we return to the same trough day after day for years, we inevitably get the itch to play a new game.

This is why TikTok exploded to 800 million monthly active users in just a few years. Yes, they also bought a lot of users through an advertising campaign of historic proportions — but that’s not the whole story. Much more importantly, TikTok is a new kind of game that people are excited to play.

And, left unchecked, it’s likely to put a permanent dent in Facebook’s business.

Social media is an increasingly zero-sum industry. In mature markets people are approaching the limit of time they can spend online, and every minute you spend on social platforms other than Facebook means lost ad inventory, lost data that can be used to personalize better experiences, and reduced likelihood of future content, which leads to worse consumption experiences. It’s a dangerous spiral. The compounding “consumption → creation” loop that drives social networks can be amazing if it’s spinning the right way, but vicious when it slows down.

So the stakes for Reels — Instagram’s answer to TikTok — are sky high.

If Instagram can’t get a substantial percentage of their users to use Reels instead of TikTok, the magnitude of this threat to Facebook’s business, now valued at $766 billion in public markets, is hard to overstate. We’re talking easily hundreds of billions of dollars in enterprise value.

So, the question is: will Reels work?

2

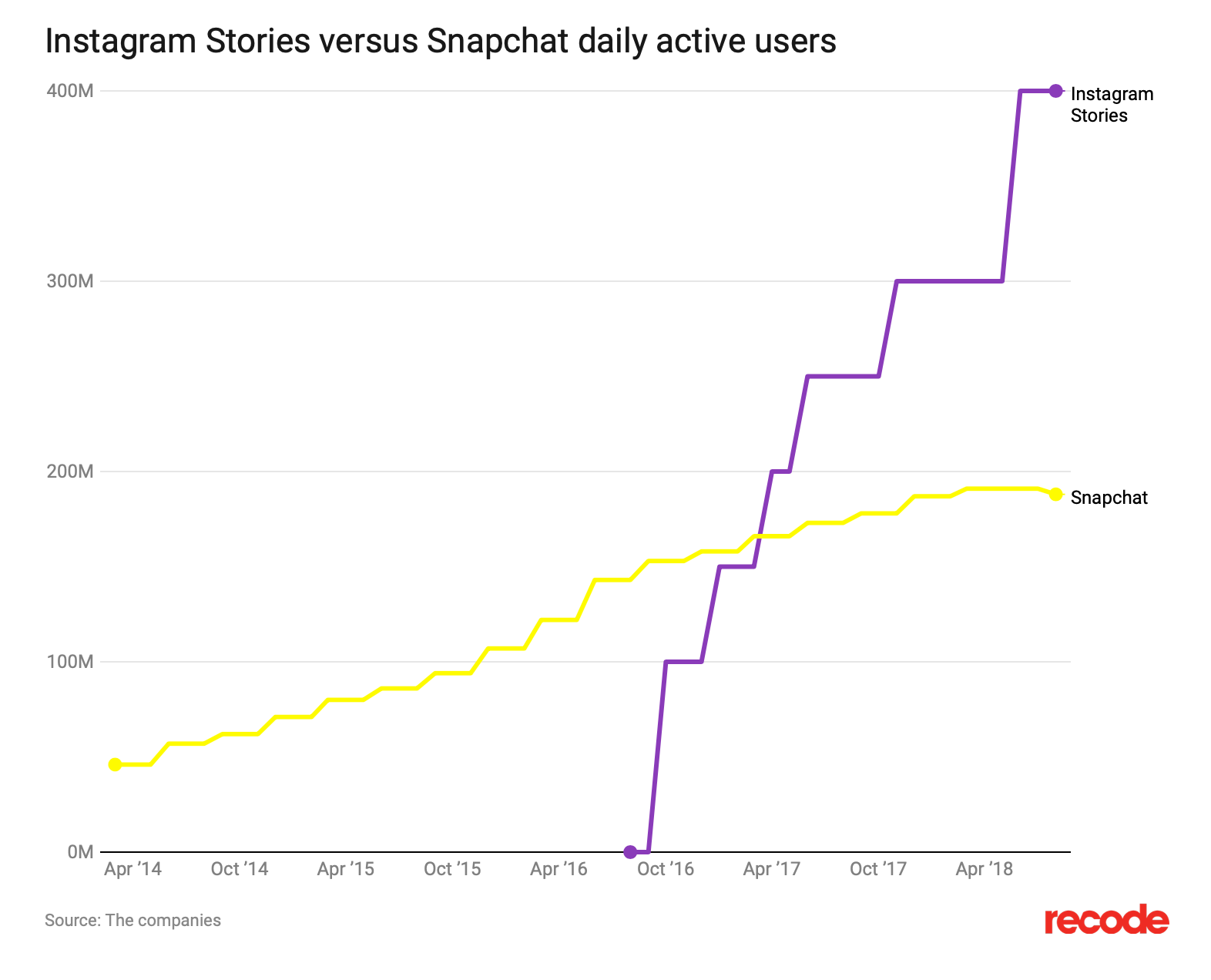

There is some reason for optimism. Here’s what happened the last time Facebook copied a competitor:

|

But past performance is no guarantee of future results, and many people learned the wrong lesson from the success of Stories.

What made Instagram Stories work was not that it simply copied a popular format within Snapchat and put it into its own product. What made it work was that it created a release valve for the pressure that individuals felt in wanting to connect with their friends and family through visuals without the heaviness of having things live permanently on their feed. It extended a core behaviour that was fully aligned with the purpose Instagram served in its users’ lives, and the structure of Instagram’s network.

TikTok is totally different. Like Snapchat, it has a novel format. But if you just focus on the format, you miss the point. The most important thing is the purpose and structure of the network. TikTok users aren’t sharing with their friends, they’re performing for the world. They’re not keeping up with familiar faces, they’re discovering new ones. It’s hard to prove this is true, but one statistic I’d look for is the percent of accounts on each network that are private. I’d guess on TikTok it’s substantially less than Instagram. But regardless of proof, to the extent that public performance is what people use TikTok for, Instagram’s network structure makes it a seriously flawed substitute.

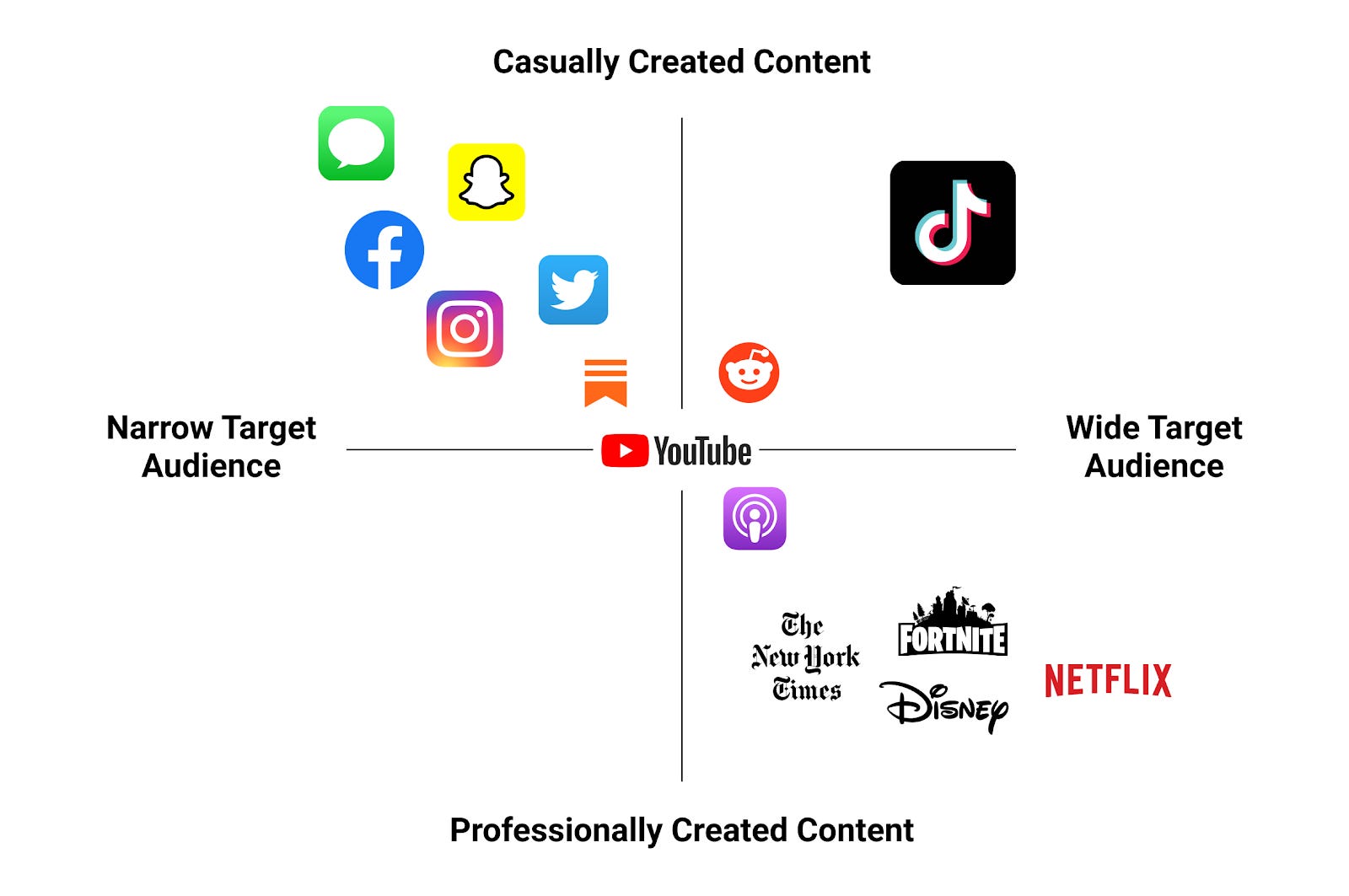

What makes TikTok so amazing is that it broke all our previous assumptions of how content can be valuable. Most companies fall along a spectrum where the wider the intended audience, the more professional the creation process tends to be. It makes sense. It’s hard to be globally interesting, so you usually need professional levels of talent and resources to do the job.

But TikTok somehow defied gravity, and stands alone as the only successful content platform where amateurs entertain the world.

|

Of course, there were hints that something like this was possible. Vine is an obvious direct comparison. YouTube videos aren’t as easy to create as TikToks, but the “viral home video” genre has a long history. There also is/was a similar culture on Reddit and Tumblr, to some degree. But hints and precursors aren’t the same thing as success at scale, and TikTok is the undeniable pioneer of the upper-right quadrant.

The reason it happened is because of TikTok’s unique network structure. On every other social network, you sign up and follow accounts from people and brands you know. But on TikTok most people just scroll their For You page, which is driven by a terrifyingly good algorithm that selects the most interesting videos for you from the entire catalog of videos in their database. Following is a secondary feature that most people use to collect the most interesting accounts they discover along the way.

Tech pundits already give TikTok’s algorithm tons of credit, but often underrate the simple fact that it has a great selection of videos to choose from. If Instagram wanted to turn their main feed into a sort of For You page — which, incidentally, they are sort of trying to do — it wouldn’t have the same feeling, because when most people post to their feeds, they are doing so for their friends, not the world. The intended audience is incredibly important.

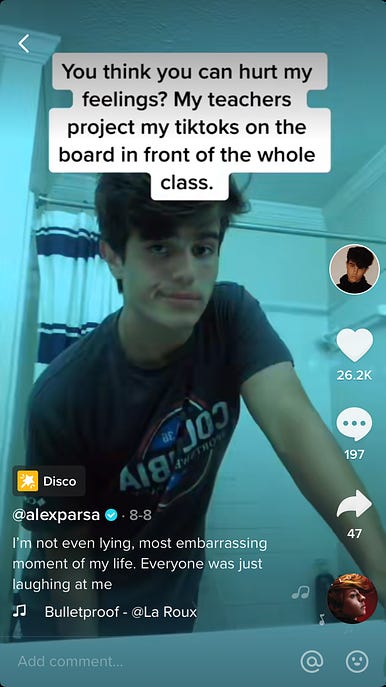

When people create TikToks, they want them to work on the For You page, so they need to entertain random strangers. What kind of content entertains random strangers? The kind of content people love to make, but might be embarrassed to show their friends. People sing, dance, make jokes, and generally do their best to look cute. This is the genius of TikTok. It takes random people who have zero followers and treats each video as an independent chance to gain distribution to an audience of millions.

And that’s how TikTok is able to keep creating stories like these:

Magic!

3

So, what would it take for Instagram to recreate this?

The double-pincer of a TikTok ban (or even its mere threat) happening simultaneously with the launch of Reels is seemingly a home run for Facebook.

Firstly, TikTok influencers have been jolted into action, urging their TikTok followers to follow them on Instagram - an app their demographic are more likely to already have than any of the other emerging replacements.

Secondly, the porting of the TikTok format onto Instagram gives all participants of the TikTok ecosystem a high degree of continuity - both for consuming and creating. The fact that a huge portion of TikTok’s user base would already have an Instagram account makes the transition that much smoother, compared to downloading a lesser known app.

Moreover, Instagram leveraging its community of influencers to start creating Reels is smart. It taps into the existing network of big influencers to spread the word about Reels and educate their fans about creating similar content.

Of course if TikTok is actually banned then it will be a huge boon for Reels. But in all likelihood, TikTok will sell to a US-based company and continue to operate.

And yes, it’s smart for Instagram to spur its influencers to create content in this new format, but as we saw with IGTV, that isn’t always enough.

How many of them will actually use Reels as a replacement for, or in addition to, TikTok? It all depends on the expected value of posting.

In theory, Instagram’s 1 billion MAUs provide a sizable potential audience for people to create content for. But Reels is currently buried within the Explore tab. It looks like Instagram is hedging their bet, which makes sense, because they can’t degrade their core experience. But the cost of added friction in the user experience is quite high.

If creators don’t feel like they have the same likelihood of going viral, this impacts the whole cycle: less creators, less creations, less diversity of content to serve, less compelling consumption experience, and even less creators. In other words, a vicious cycle.

And it’s not just the consumption experience that’s buried. The creation experience, too, is... less than obvious.

This is a classic example of complexity convection. Products get more complicated as they age. It can be great for power users, but daunting for new ones. If I were Instagram, I’d pay close attention to this. It creeps up on you.

4

Ultimately, the friction involved in creating and consuming Reels isn’t the biggest problem. Worse is that the inclusion of Reels in the Stories space starts to confuse the purpose of the app.

The mental model for going into the Stories space was to create ephemeral content for your followers. However, Reels content is not ephemeral, and if it’s actually supposed to be just like TikTok, many users might not even want their friends to see it.

Unless you’ve actually spent significant time on TikTok, it’s easy to underestimate just how different Instagram and TikTok’s cultures are.

The biggest obstacle Facebook has to overcome to make Reels successful is that the type of content that makes TikTok amazing is the stuff people don’t want to post in an environment connected to their real-life friends.

|

Facebook and Instagram are about sharing with your friends, but TikTok is about creating something for the world.

Creativity depends on risk. It’s about putting yourself out there. Looking weird. People are only willing to do that in safe environments. TikTok’s unique network structure helps ensure this safety. All you have to do is create an account and publish videos.

Which brings us back to the quote we opened the essay with:

Variety: When this all happened, you were still in high school and living in your hometown. How has your life changed?

Charli D’Amelio: At first, it was really uncomfortable because when TikTok started, it was kind of like, “Oh, you’re on TikTok? That’s weird.” So I wouldn’t tell people.

TikTok will bypass your real life connections to find people who’ll love the real, weird you. It is, in many ways, the anti-social-graph.

An odd fit within Instagram, to be sure.

5

So, what can Instagram do?

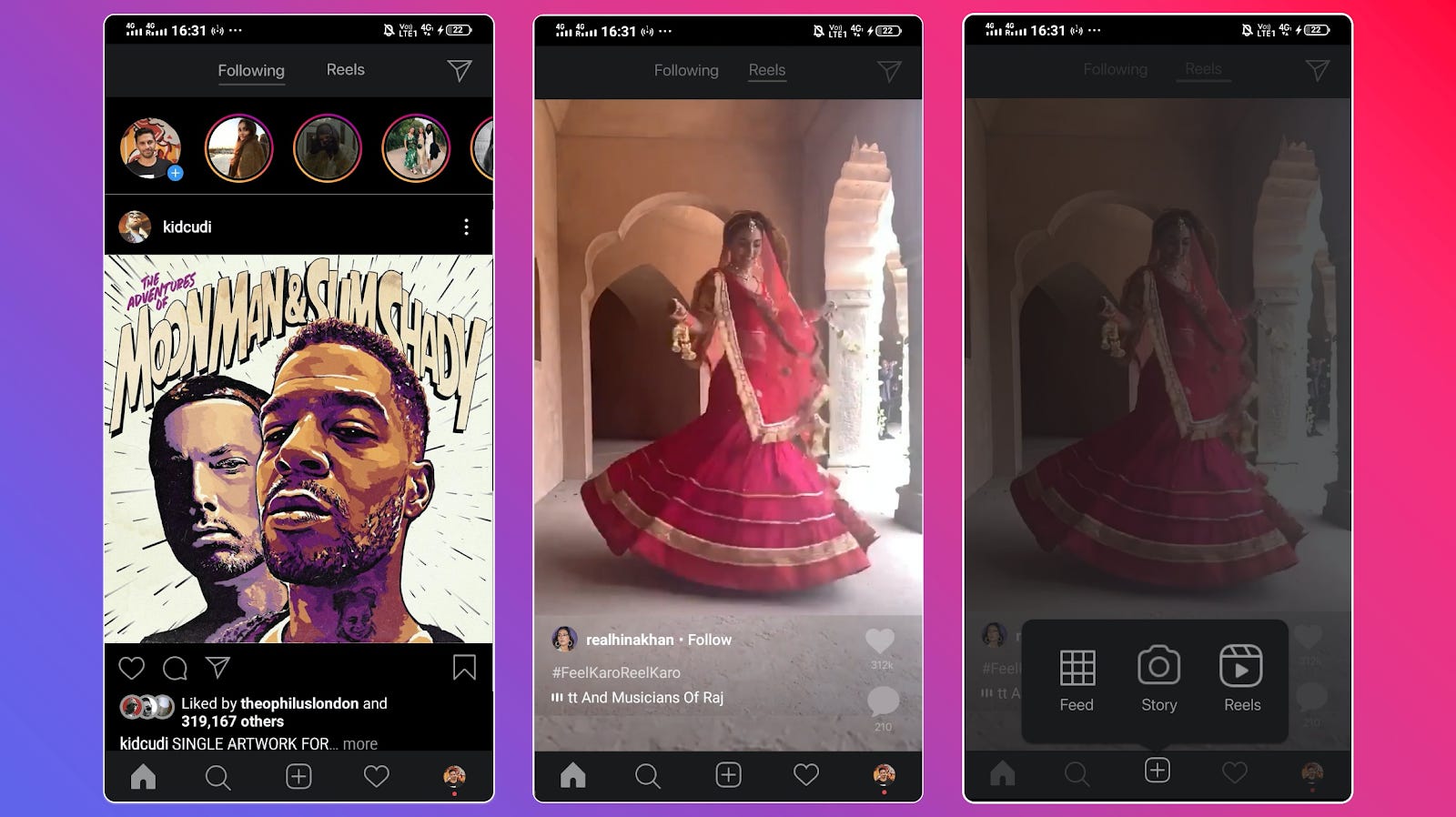

Well, at the very least they could design Reels into the experience in a more frictionless way. Here’s our take on what this could look like:

|

Here we suggest two changes:

Add Reels to the main tab, rather than the explore tab, and make it just a swipe away. This will feel familiar to TikTok users and reduce the friction to finding Reels content.

When a user taps the “create” button, ask them what they want to create before popping them into a complicated interface. The options are: Feed, Story, and Reels.

We bet these changes would increase time spent consuming Reels and number of Reels published per day — without harming the core Instagram experience.

But of course there’s still the problem that the TikTok network structure and purpose is somewhat antithetical to Instagram. How do you fix that? You don’t. Instead, you allow Reels to become more of its own thing. You embrace the fact that people are mostly going to create normal Stories type content, but in a slightly different format.

Instagram faces a difficult decision here. Do they build features that make sense internally and address real desires and problems their own users face? Or do they attempt to recreate the unique magic TikTok has cultivated?

To us the choice is clear: as an app becomes more bloated, more unfocused, prioritising monetisation over intrinsic user experience, the bigger the opportunity becomes for a simplification, an unbundling, a new experience built on a core user insight.

Choosing to remain true to Instagram’s core purpose requires conviction. It requires a willingness to accept certain limits. It wouldn’t be popular in the boardroom. But it’s the strongest move.

Instagram should compete to be unique, but it’s competing to be the best.

What’d you think of this essay?

Neer Sharma writes about consumer product at aha.substack.com and co-founded HaikuJAM, a social writing game.

Nathan Baschez is the author of Divinations and co-founder of the Everything bundle.

Thanks to Shreya Sudarshana for her invaluable feedback on this post!

Go deeper

If you liked this post and want to read more, I’d recommend reading my post on trade-offs. The main reason why Instagram can’t copy TikTok is because there are just too many trade-offs they’d have to make. In order to be better at serving TikTok’s purpose, they’d have to become worse at their own core raison d’etre.

(The trade-offs post is for paid Everything bundle subscribers only. If you can’t afford a paid subscription, email me and we’ll work something out!)