Hey, Nathan here! Remember a few months ago when we published a wonderful essay on LinkedIn’s ridiculousness? It was one of Divinations most popular posts ever, and it was written by Fadeke Adegbuyi, a brilliant observer of internet culture who also is a senior marketing manager at Doist. Today I’m thrilled to share with you Fadeke’s latest work—this time examining our obsession with identity through the lens of a Twitter bio tracking app called Spoonbill. Enjoy!

Elon Musk updated his Twitter bio 23 times in 2020. He last changed it on February 4, 2021 at 6:31 AM PST. A few versions include “Born 69 days after 4/20,” “SoundCloud Rockstar,” “Budgie Smuggler,” and “#bitcoin.” I didn’t spend months stalking Musk’s page, developing an encyclopedic knowledge of his time spent in the Twitterverse. I looked it up on Spoonbill.

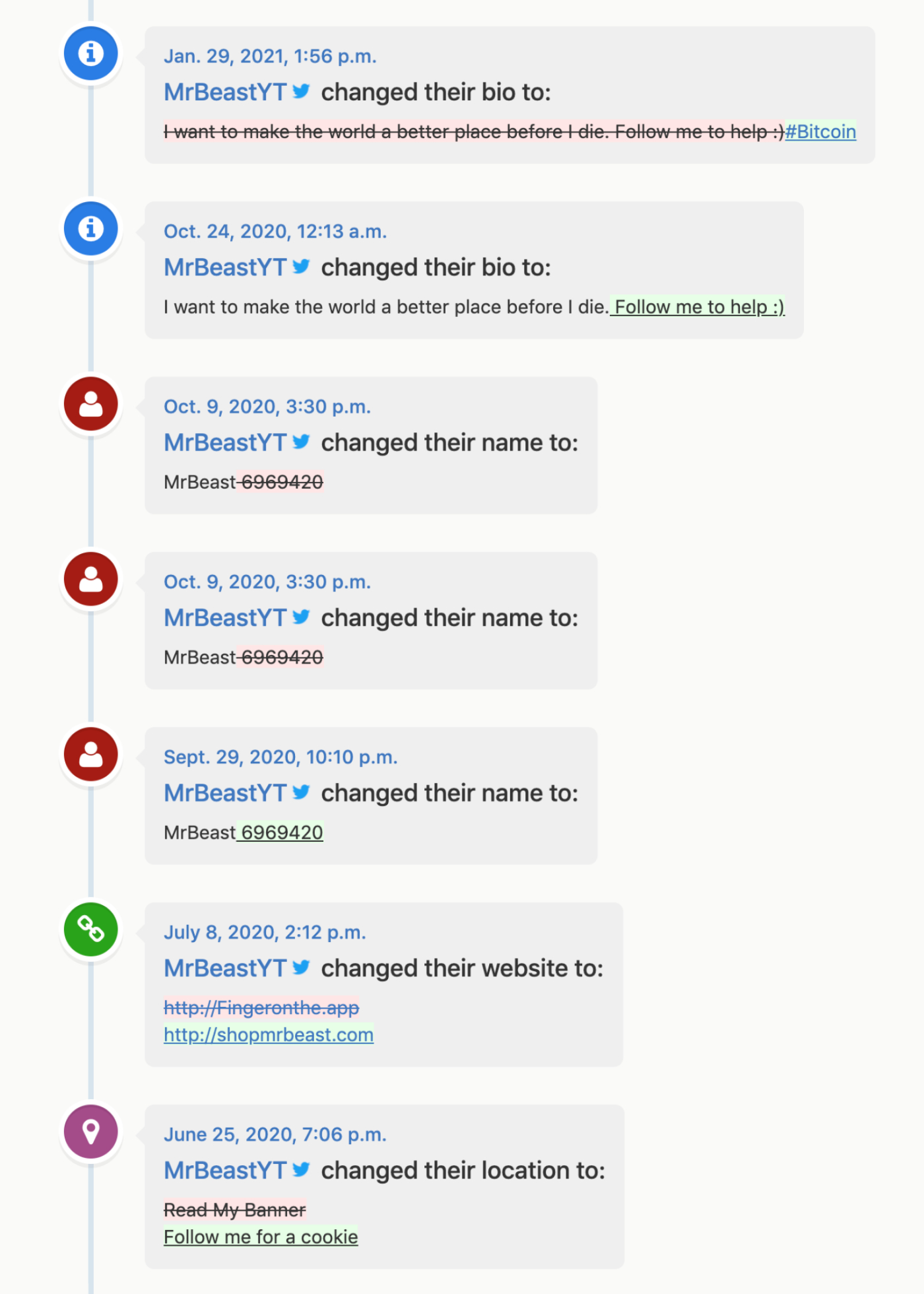

I could use the app to give you similar information on any celebrity or public figure with a Twitter account. Or I could use it on you. If I wanted to, I could see all the changes you’ve made to your profile since you first signed up: your name, your location, your website, your pinned tweets. Spoonbill’s creator, Justin M. Duke, describes the app, which has nearly 93 thousand users, as a “tracking tool for online metadata.” Over 45K of those users have signed up to receive daily emails that aggregate updates across all the Twitter profiles they follow. The open rate for these daily emails hovers around 55%, well above average for email campaigns.I asked Hunter Walk, a Partner at the seed-stage venture capital firm Homebrew and an avid Spoonbiller, why he uses the app :

"It's fun to see people wordsmithing their bios, changing the order of the portfolio companies they list based on startup performance, subtly announcing personal life changes...Instead of letting Twitter decide what's worthy of notification, I get to see every change and decide for myself what's interesting, often with context that the algorithm is unaware of."

The tracked changes that Twitter’s algorithm might register as neutral additions and subtractions can indeed be revealing to onlookers. Spoonbill captures what the people we follow are changing their bios to express; an investment exit, a tongue-in-cheek joke, or the end of an internet cult affiliation.

Social apps have made creepers out of all of us. Whether it’s scrolling to the start of someone’s Instagram feed or looking through Venmo transactions, we’re constantly peering into others’ online lives. Spoonbill not only satisfies our tendency for online lurking, but pushes it into voyeur territory; surfacing what’s meant to be hidden is intimate in a way that scrolling a timeline isn’t. The tool provides a glimpse into the specific ways we represent ourselves to the world, the unseen effort with which we express our identities, and how the uncanny feeling of being watched informs our sense of self.

Twitter Tracked Changes

Twitter is an interesting observation ground for online identity. Snapshots at Big Sur are meant for Instagram’s photogenic feed, while professional milestones belong on LinkedIn’s alternate universe. But in the Twitterverse, life and work converge. People are just as likely to share career news as they are to live-tweet a Netflix binge; professional gripes commingle with criticism of political leaders; snark and sincerity live side-by-side.

Twitter’s bio section, then, is a tall order: compress your entire identity into a single line item. Many use the space to convey their own complexity––smart yet funny, accomplished but approachable. Society has progressed past the need for the phrase “works hard, plays hard,” but that’s what we’re trying to convey in our own personalized way: we contain multitudes. We are real.

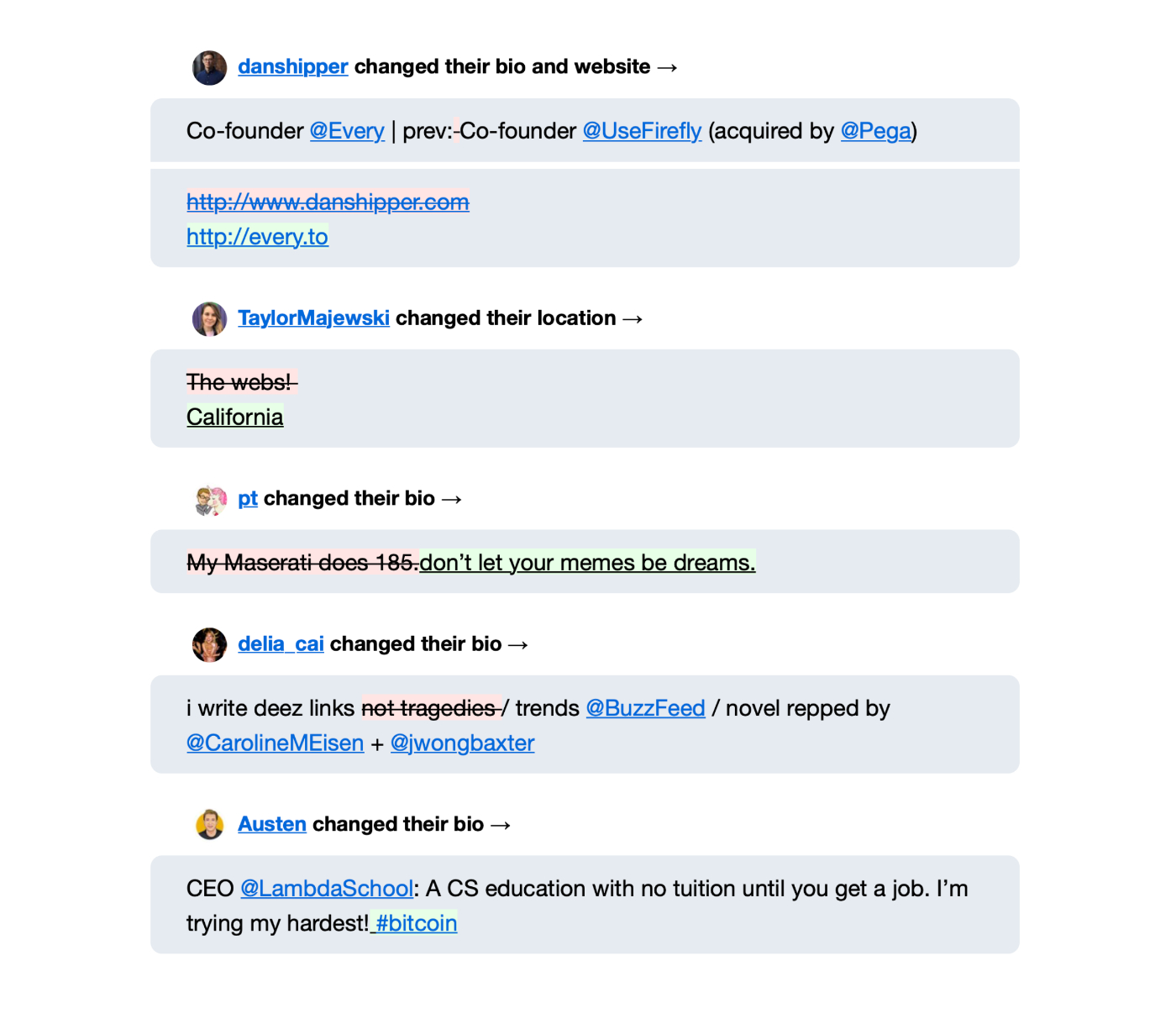

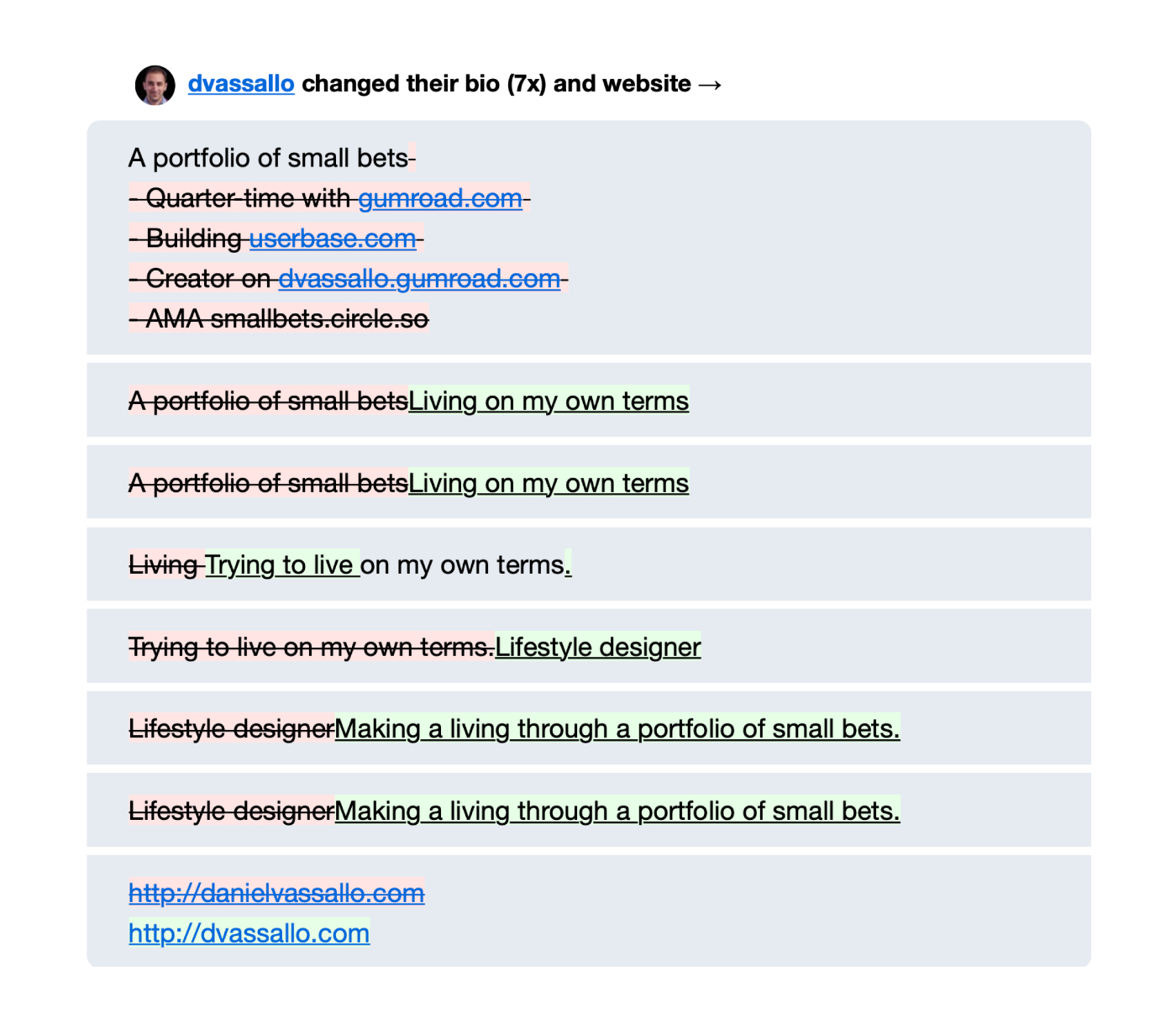

Spoonbill reveals the way that people play with their latest positioning of self, carving out character space for their newly important aspects of identity.

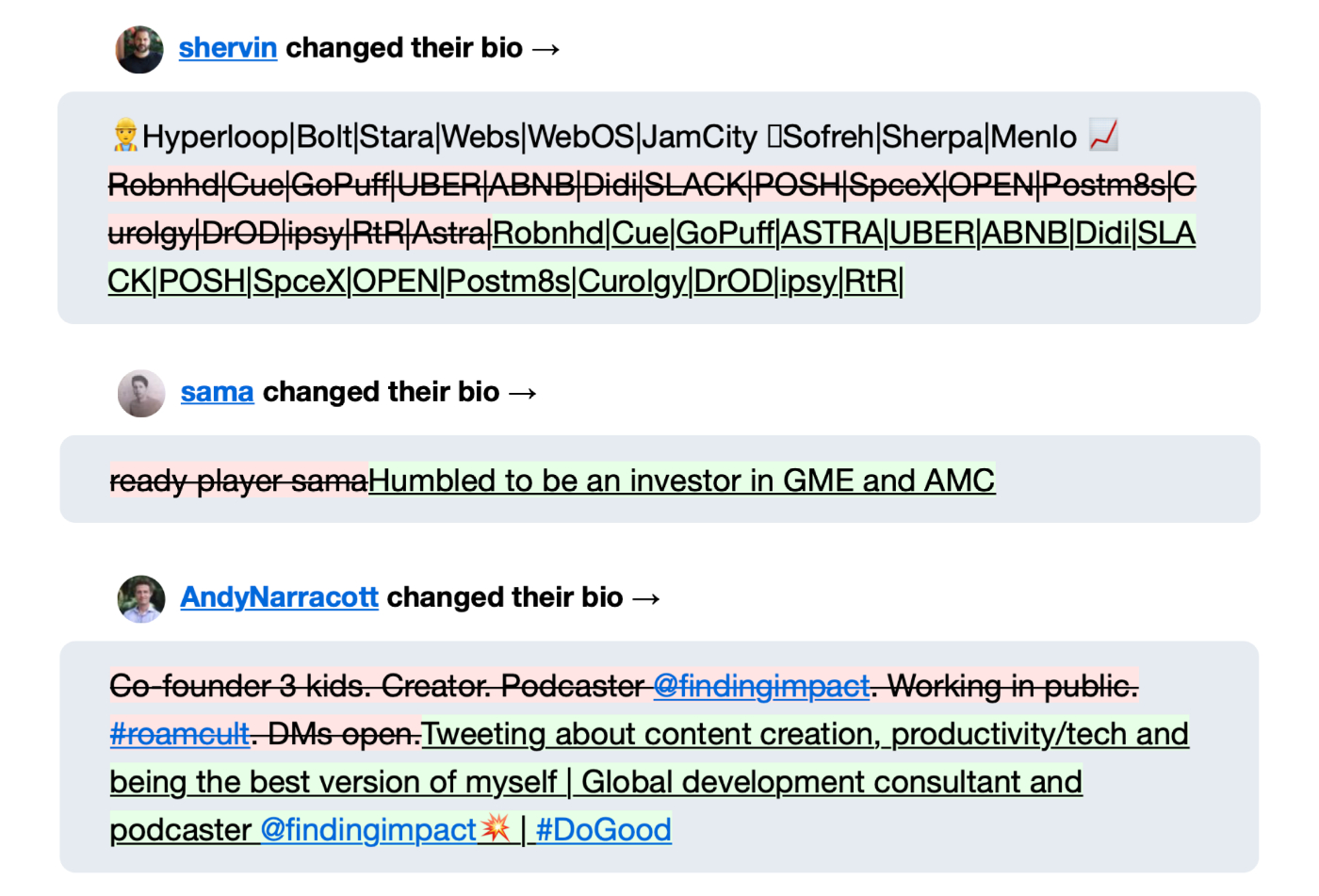

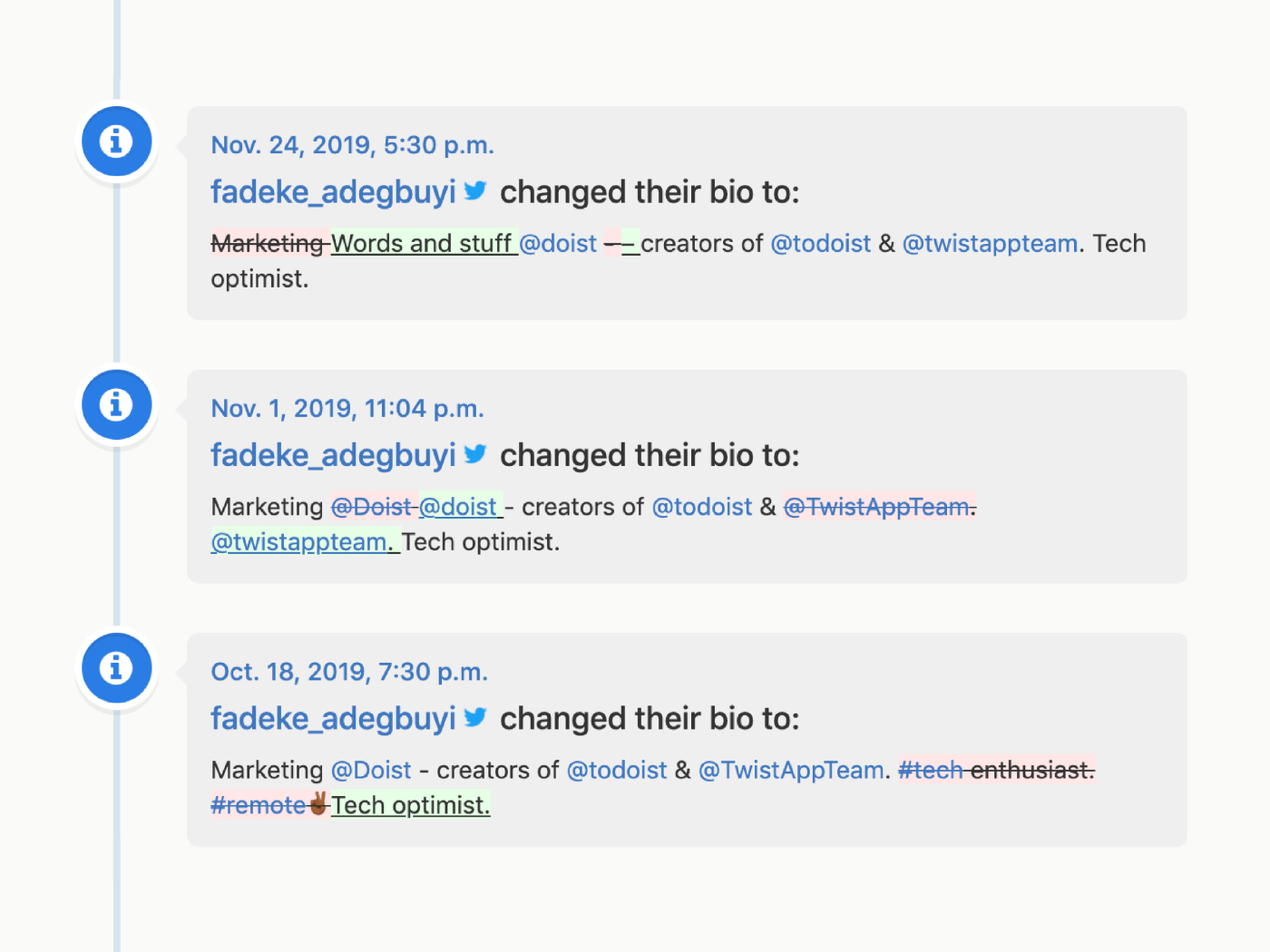

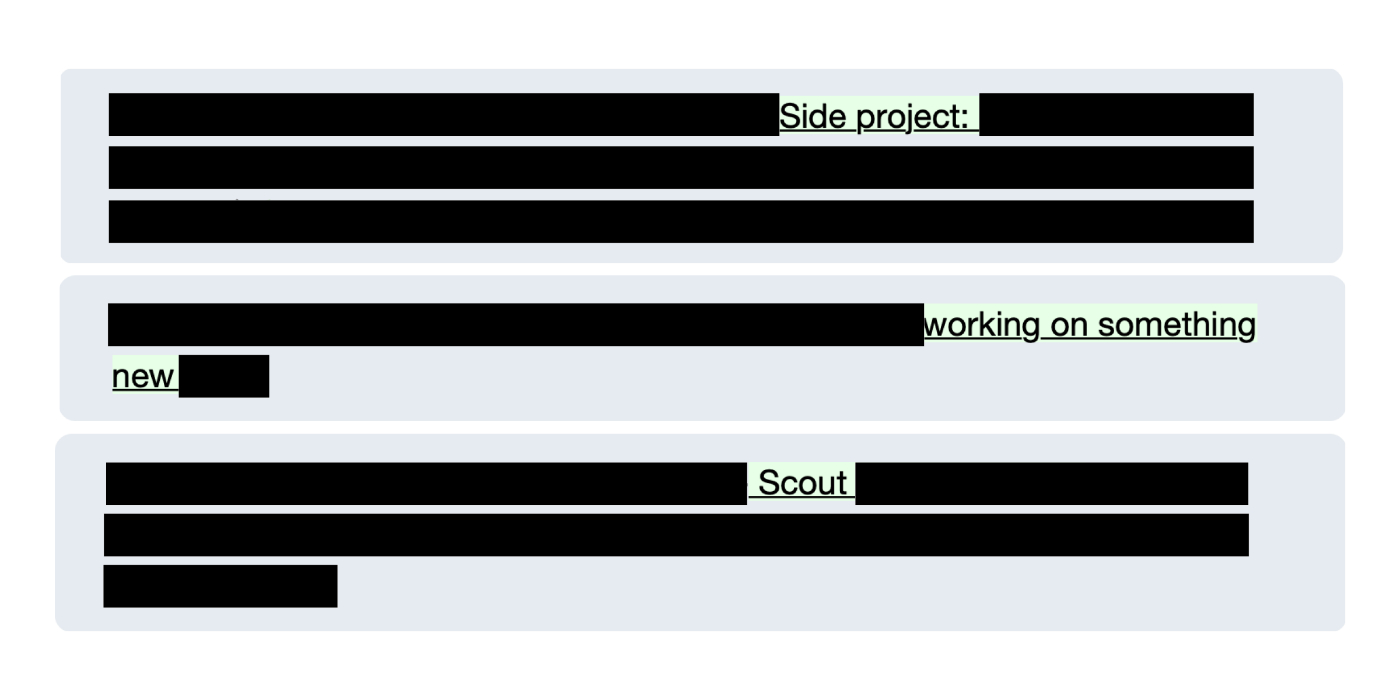

Hustle culture looms large and professional accomplishments convey worth. In turn, notable work, career highlights, and impressive affiliations take center stage in our Twitter bios, the structure and grammar of which are heavily coded. Freelance journalists add and shuffle their bylines, arranged in order of prestige –– @nytimes is meant to come first. In my corner of Tech Twitter, where optionality is king, it’s now effectively a meme to be “starting something new,” marked increasingly by the addition of “Substack:”, “Scout:”, or “Side project:” to one’s bio. Users adding “permanent student” or “forever learning” to their bios aren’t pupils at cruel and unusual institutions, they’re signalling intellectual curiosity.The ability to see Twitter bio updates across hundreds or thousands of profiles over time make Spoonbill updates insightful in aggregate. Certain patterns and conventions emerge.

Spoonbill’s creator has observed interesting trends in his app:

"On an individual/corporate basis, a particularly fun one is seeing angels and investors tinker with the parts of the portfolio they choose to highlight. A very classic example of this was the sheer number of firms and investors who removed things mentioning WeWork during, well, the period of time that you didn’t want your name associated with WeWork."

WeWork reached a $47 billion valuation in 2019, but cancelled their plans to go public after their IPO filing drew questions and concerns. In a bio block that’s meant for selling ourselves to a potential follower, a failed investment takes up valuable real estate. But while WeWork investors might wish we would all forget their involvement as quickly as they hit “save” on their new bio, Spoonbill always knows.

In that same 160-character space, we’re also meant to declare our commitment to cause: political, social, or economic. Often, emojis will do:

If you watch Spoonbill updates closely enough, they suggest that the labels and descriptors we choose to signal our allegiances can be fleeting, our attention spans short. As COVID-19 spread throughout the world in early 2020, many updated their bios with their own messages about the virus, encouraging their followers to take some form of action:

But almost as quickly as these bio changes were made, they were unmade, individuals returning to their regular profiles. Less charitably, people just got bored; short-term vigilance surrounding the virus eventually led to a return to normal life for many. More charitably, the longer the pandemic wore on, identities once swaddled in concern for the virus eventually needed some wiggle room.

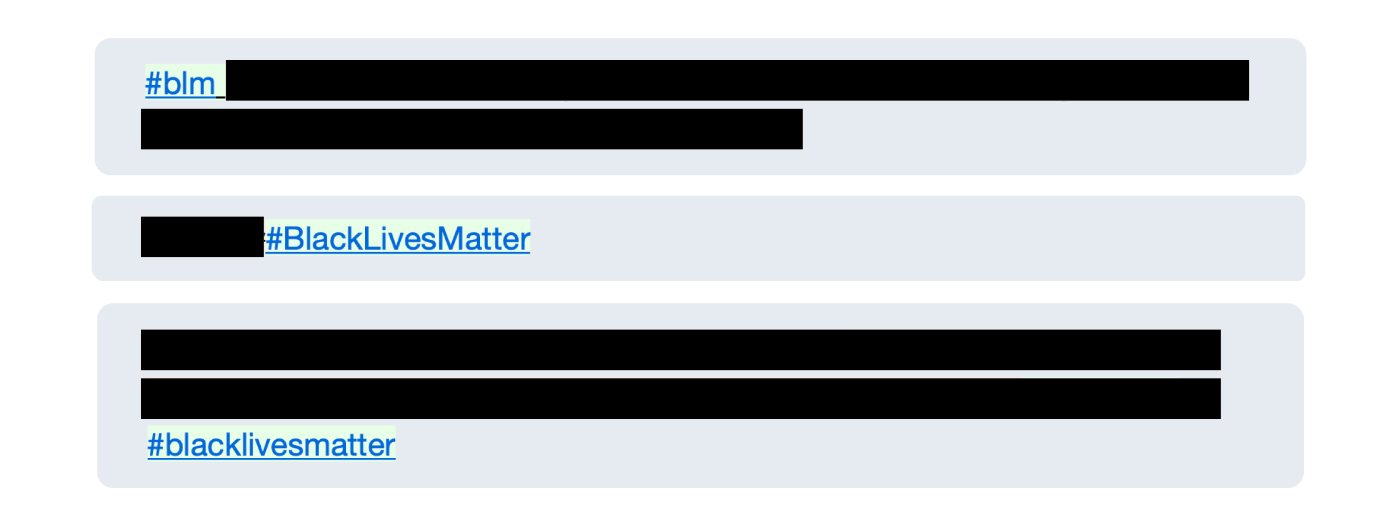

Last year, as racial tensions bubbled to a boil throughout the United States and set off an international cascade, Spoonbill revealed how Twitter bios were used to show support for what was top of mind––or a stance on what was top of the fold:

As time went on, it was jarring but predictable to see lines through phrases like “Black lives matter” across swaths of profile updates in my inbox.

Politics similarly finds its way into our descriptions of self. With the 2020 U.S. presidential election, many translated their desired vote on the ballot to their bio:

The story has already been written, and you know what comes next: dashed presidential dreams translated to crossed-out candidates. Adding presidential hopefuls or even political parties to how we identify can be an exercise in disappointment. Disappointment is inevitable (after all, there can only be one). But seeing how long people hold on to their hopefuls was interesting; some still signalling long after their candidate had dropped out.

These tracked changes of our online selves provide a glimpse into the specific ways we represent ourselves to the world, how society manages to infect our identities, and, what we value—or what we want to be seen as valuing.

The Uncovering of Tacit Labor

Spoonbill uncovers the tacit labor involved in our quest for the perfect personal positioning. In describing the way online influencers take effortless-looking selfies that are actually quite effortful, Dr. Crystal Abidin (aka wishcrys), a researcher and “anthropologist of influencer cultures” (according to her own Twitter bio), coined the term “tacit labor” as:

“A collective practice of work that is understated and under-visibilized from being so thoroughly rehearsed that it appears as effortless and subconscious.”

You don’t need to be an influencer to know the labor involved in taking and selecting a selfie. Getting the right light, angle, and expression are just some of the considerations made while snapping and choosing from the photos that fill our camera rolls. After selecting the winning shot, we leave behind a stream of rejected selfies, never to see the light of day; the tacit labor stays hidden. After a photo has been cropped, filtered, and face-tuned, a refined “self”-ie joins the feed, adding to our curated online image––polished, carefree, or somewhere in between.

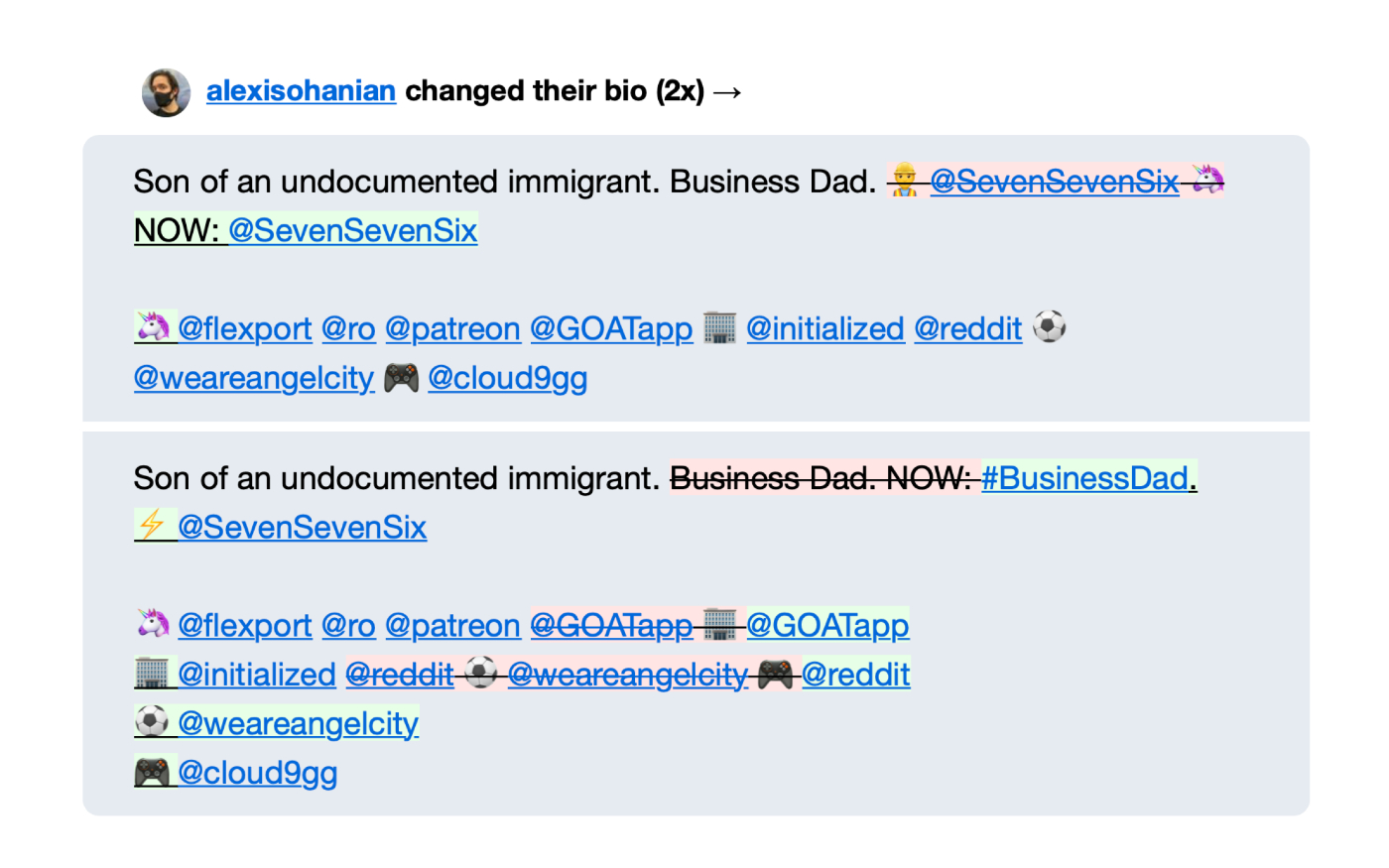

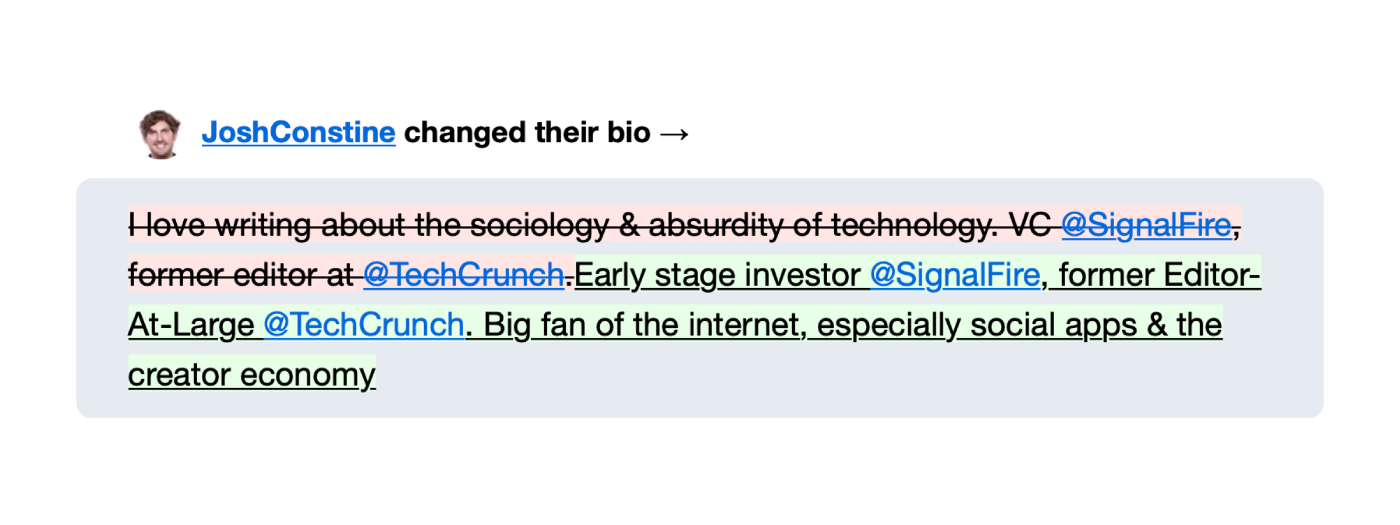

Just like we strain for the perfect selfie, we tinker to find the perfect bio, treating it as a personal sales pitch and making micro edits to what we represent and “who we are.” Spoonbill catalogues every time-stamped keystroke and tracked change––from the removal of a single stuffy period to self-consciously swapping “Marketer” for “Storyteller” and reverting back again. Like the photos in your camera roll, your current Twitter bio has left––for Spoonbill users to see––a wake of rejected selves.

Spoonbill reveals the surprising scale and frenzying frequency with which all kinds of people make these online edits. We add in emojis, expand and shrink our past affiliations, and flirt briefly with humor, adding clever one-liners before eventually reverting to something more serious. It’s effortfulness on display. Seeing people iterate on their identities in Spoonbill, switching too-formal uppercase for carefree lowercase characters, makes our desire to control how we’re perceived clearly legible.

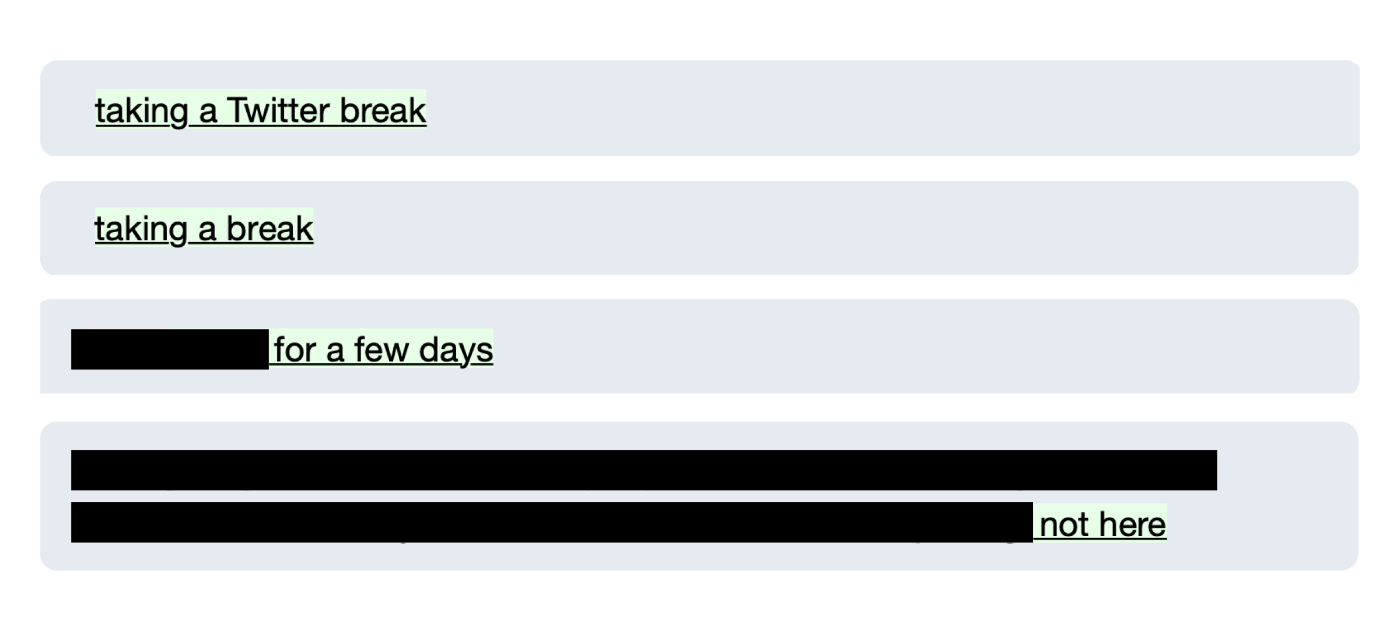

The time spent laboring over this minutiae can appear silly and perhaps a bit sad: who cares? But tools like Spoonbill are irrefutable proof that people are watching. Even at the most minuscule of levels, people indeed care––if not about you, then at least your presentation of you. The underlying fear driving some of this status line anxiety, that people will point and laugh if we don’t get it just right, is unlikely but not unfounded. Nearly as bad is the idea that nobody might care at all, disinterested in our personal pitch. But if we get the words just right, people might think we’re interesting––worth the follow.If this all feels exhausting, it’s probably because it is. It’s likely best to opt out, and some very much do. They leave their Twitter bios the same indefinitely or don’t have one at all. Not playing beats the game of constant reinvention. Existing in a digital space comes with a particular pressure to maintain an online identity that lives up to the bios we so carefully craft. After some time, this can be burdensome.

A common catchphrase on Twitter is “I can’t believe this website is free.”

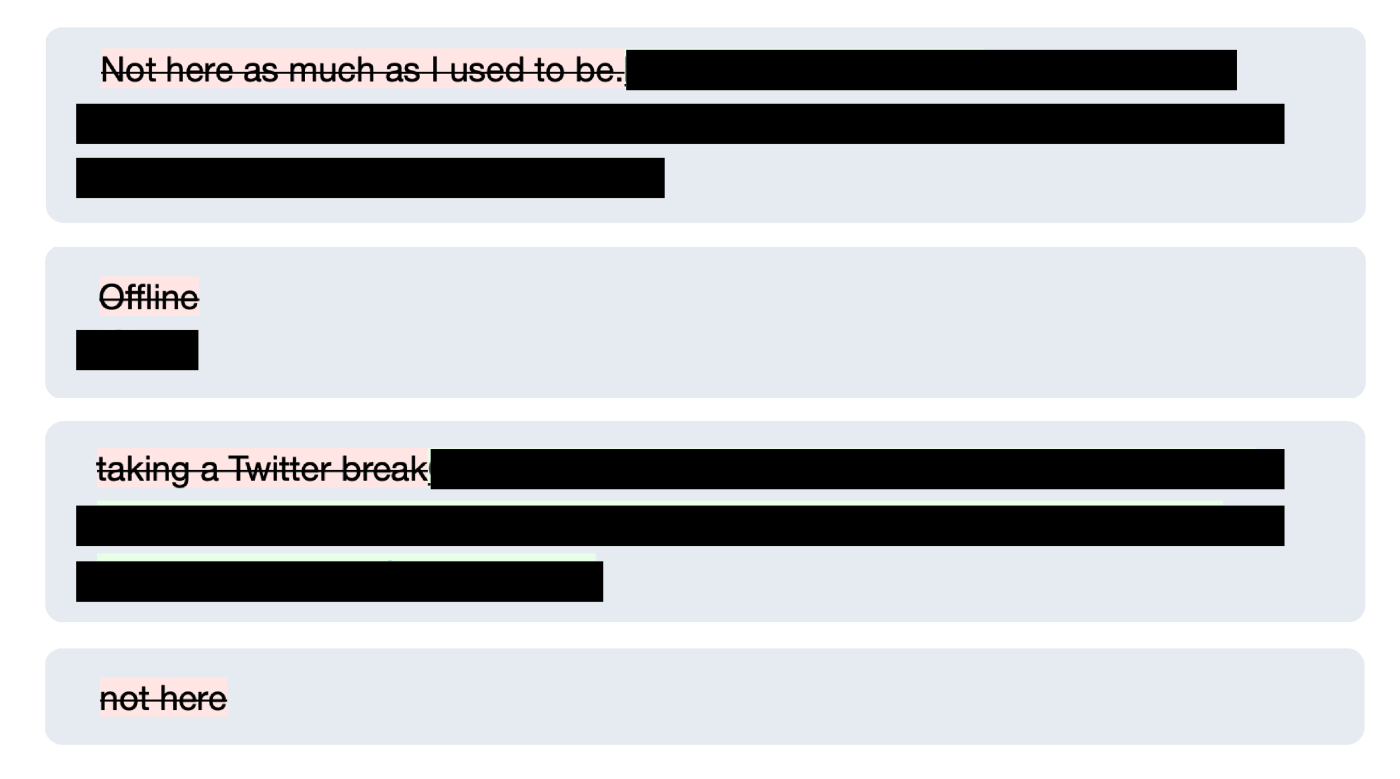

But there’s a cost to maintaining our online avatars and for some the price feels too high from time to time, leaving them running for the exits, from the online work of it all, a reprieve from our unpaid performance jobs. Signalling isn’t free. Unsurprisingly, the bios tell the tale:And yet, as abruptly as the exit comes the return. Many people don’t cross the 48 hour mark before they’ve reverted to their old bio, back for their regularly scheduled programming. To steal a fitting phrase, “I hate it here, see you tomorrow.”

The Interplay Between Privacy and Personality

Nearly a decade ago, Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey penned a piece on the online phenomenon of frictionless sharing. They make an interesting and seemingly prescient argument that the internet is full of “digital paparazzi” invisibly collecting data, tracking users, and surveilling us all. In turn, this shapes how we act in front of the glare of the cameras.

In 2021, data collection has only gotten more sophisticated and discussions surrounding online privacy are ubiquitous––our online monitoring no longer comes as a shock:

“Of course, the subject of invisible digital-paparazzi documentation is not always completely inactive in the documentation process. Many of us know, to some degree or another, that we are being tracked. Celebrities know that paparazzi might be present at any time and place and learn to behave as if they are always being watched...we are increasingly aware that we are being documented, and thus increasingly calibrate our behaviors as such.”

In the wrong hands, this metadata could be dangerous––a Spoonbill user might be an internet anthropologist, a journalist, a casual creeper, or an obsessed ex. Tools that surface personal data should be thinking through worst case scenarios involving the most nefarious actors––what starts as internet creeping can descend into real-life stalking. I asked Duke about any safety concerns regarding the location change tracking in Spoonbill:

“Yes! While Spoonbill purposely doesn’t track tweet-level location data, I think there are concerns around tracking any sort of change, location, and all the others included (though in my experience location is actually overly noisy — I’ve had more removal requests for name changes than location changes)...I think a lot of people are very angry at [the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation] because, frankly, it is annoying — yes, the cookie consent banners are old hat, I get it, but data is an important and sacred thing. It’s extremely important to own your own data! I think laws, not best intentions, are the right mechanism to dictate how apps like mine need to behave with regards to any sort of safety or privacy concern.”

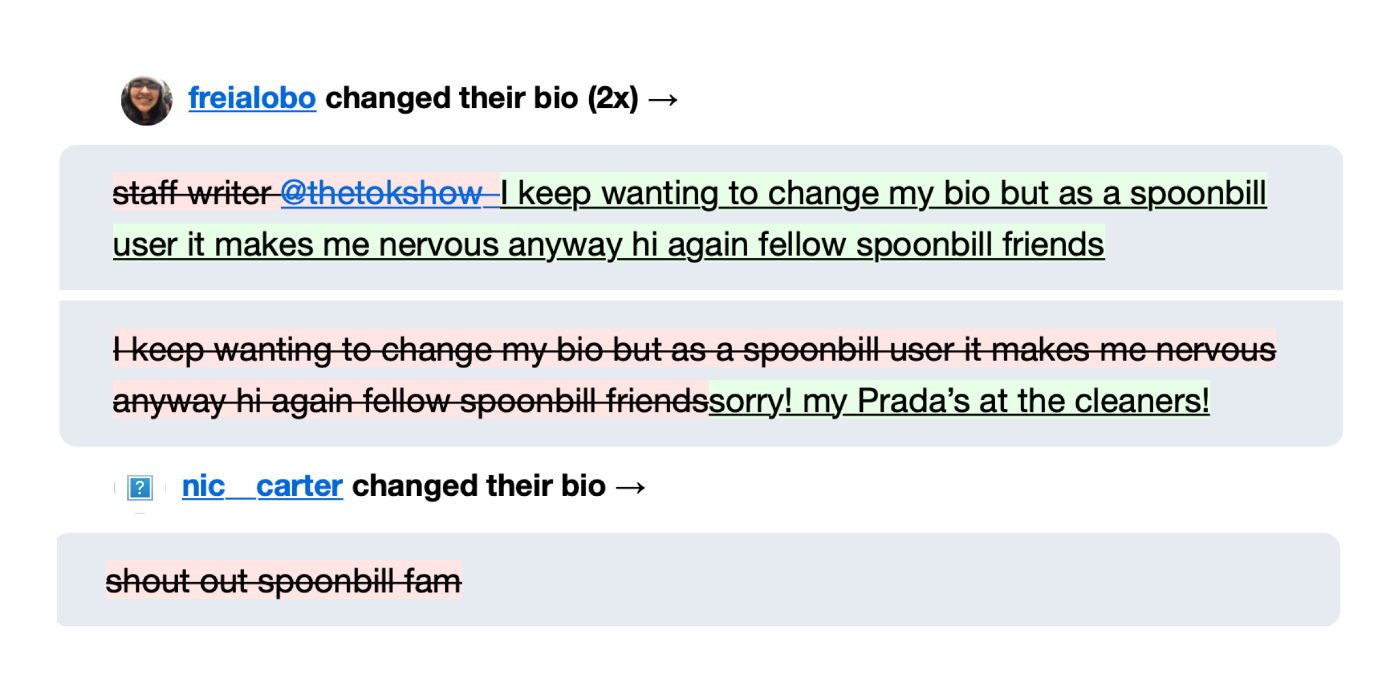

While these are Big-P Privacy concerns, there are the little-p privacy concerns, too. In Spoonbill, the little changes we make to our Twitter profiles, seemingly hidden from view, are actually tracked, made public, and delivered to people’s inboxes. While I tend to think this is mostly benign, it’s interesting to ponder on Jurgenson and Rey’s thesis of how our behaviours are increasingly dictated by the erosion of our privacy and our knowledge of being watched. Some Spoonbill users, aware of being observed, acknowledge and take part in the game of it all:

Not everyone has quite the same humorous response to the uncanny feeling of being seen. In defining ourselves online, we draw from the influence of the internet, often contorting in ways we anticipate will be acceptable to an online gaze. But at a certain point, our online self drives our personhood IRL too. Plastic surgeons have been inundated with clients asking them for what Jia Tolentino calls “Instagram Face,” a look based on the effects of FaceTune filters.

It’s not hard to imagine how our social media identities affect other aspects of our selves, especially in the increasingly irrelevant real world. As both work and life moves “remote,” the most we see of even our loved ones is online. As more and more of who we are exists only on the internet, we alter our offline lives with the anticipation that the highlights will be uploaded, photos and statuses that confirm who we say we are, and that we’re still here. And as we grow more socially aware, in part because of what comes to us through our feeds, we become more anxious and exacting, refining our internet identity and A/B testing our selves, in search for the fit that feels––or looks––like us. We treat our identities like software, continuously debugging in order to avoid obsolescence in an online world that’s increasingly difficult to differentiate from the real one. We’re in constant iteration, finding the best way to describe ourselves in our own words.

This piece was edited by Rachel Jepsen, with help from Natalie Toren and Dan Shipper.