Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In this episode, we explore:

Low T

Work-life blend

Mimetic traps

Face to face

Creating rituals

The male monkey dance

Let’s dive in!

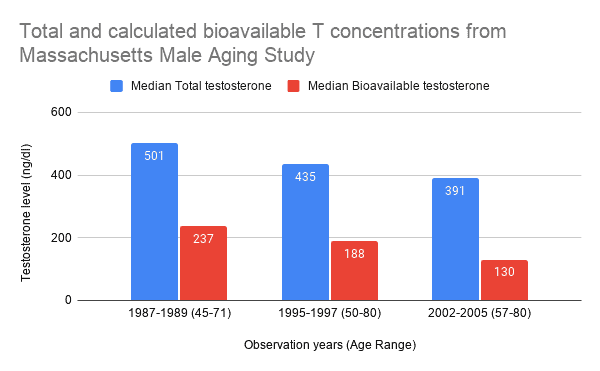

Fitt Insider had a great edition on Low Testosterone, an essential topic for men’s health & wellbeing.

Testosterone replacement is taking over the men’s health conversation… again.

Fountain of Youth

A vital hormone, testosterone affects men’s fertility, libido, body composition, and overall well-being.

Medicine x marketing. Testosterone boosters have become a multi-billion-dollar industry. Yet, many experts question the rise of unregulated supplements and widely accessible hormone prescriptions.

The testosterone therapy market is expected to reach $3.3B by 2027.

Between 2003–2013, testosterone use quadrupled among 18- to 45-year-old men in the US.

Clinically diagnosed, hypogonadism is a condition in which the body doesn’t produce enough testosterone.

Conventional wisdom says testosterone declines naturally with age, dropping about 1.6% per year starting in the mid-30s. But, scientists and entrepreneurs are pushing back on this notion.

Citing lifestyle factors, including smoking, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and environmental toxins, many are quick to point out that the decline is unnatural and largely preventable.

A step further, optimizing testosterone levels has become part of the high-performance movement, taken to enhance longevity, energy, and aesthetics.

Cashing in. During the mid-2000s, pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed testosterone treatments with TV ads touting an elixir of youth.

A successful campaign, testosterone prescriptions grew 300% in the first half of the decade, with drugmakers notching billions in sales.

A red flag, only a fraction of those men were diagnosed with hypogonadism. Worse, many others never had their hormone levels tested at all.

In 2014, the FDA warned against these treatments, resulting in thousands of lawsuits claiming drug manufacturers failed to disclose serious side effects.

The best thing you can do as a man is to get your testosterone checked and try to increase it naturally at first. Even if it’s low, there are many ways to increase it naturally. Prescribing TRT to men who don’t need it has become a lucrative business, but it’s not benefiting you because you can’t opt out once on TRT.

Here are some ideas on how to increase your testosterone naturally; it’s possible and the best way to go about it in most cases.

Pair with: TRT WAS A MISTAKE & Stay Natty Bros

Also pair with: Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Threatening Sperm Counts, Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race

I never liked the term work-life balance. This piece managed to decipher why.

Attempts at “Work-Life Balance” are doomed before they start.

The term “balance” suggests there’s some invisible scale held aloft by Father Time on which we need to allocate grains of sand between our Work and Life buckets. Too much on one side, and the scale tips, sending us careening towards unemployment or a Pez-dispenser of Xanax.

Confronted with this dichotomy, we consume endless media clawing for a solution to our frenetic see-saw of priorities, looking around each corner for the One True Plan, which will deliver us to happy stasis.

Sometimes, we may stumble upon it, but the equilibrium never seems to last. We settle into the new routine as a well-oiled machine for a season, and then the wheels start to come off. Sand piles high on the work plate, and our daily sine-wave of caffeine and alcohol magnifies with it. After a midday cry in the bathroom or an I’m-totally-never-drinking-again-for-real-this-time weekend, we must admit the balance is broken and return to the trough of knowledge for a new solution.

There is no solution, though. The language we used to define the problem made it impossible to solve.

It seems that most of the problem comes from using the wrong term.

The problem with “work-life balance” is the term “balance” itself.

When you hear “balance,” you immediately think of a dichotomy. For two things to be balanceable, they must be at odds with each other. Lowering one side of the scale must raise the other side.

When we describe work and life as things to be balanced, we are suggesting that work and life are at odds with each other. More time or energy allocated to work means less time and energy allocated to life.

This is obviously absurd, though. Work is just another part of life like family, community, food, fitness, creativity, travel, fun, spirituality, etc.

Instead of aiming at work-life balance, try to see how areas of your life can complement each other. It’s a puzzle that you try to fit together.

Work is not something to be balanced against everything else. It’s one of the many buckets in our life, sometimes the most important one if you’re hardwired that way, and something we should figure out how best to integrate with the other areas in a healthy, supportive way.

We’ve already talked about mimetic traps a few times on The Long Game, but I really enjoyed this article, so I thought it was worth sharing. It resonated with me as I had a similar experience studying physics, not for the beauty of it, but because it felt prestigious, and then sticking with it for no other reason than being competitive and not accepting of losing.

I’ve been a graduate student in physics for almost three years, but I only recently figured out why. I had to tackle a simple question do so:

Why does this matter?

I realized that I’d never forced myself to answer this honestly. As Paul Graham has pointed out, these systematic gaps in conversation should raise suspicion — they often indicate when you’re wrong about something important. I was wrong in thinking that my work mattered to me, and I avoided asking myself this question because I knew the answer would be painful.

One afternoon, while moving out of an apartment, I came across a cardboard box packed with binders and paper folders, full of notes accumulated over the past year. As I let it fall in front of the door, a thought dropped into my head and stuck there: none of this means anything to me. This was, nominally, the fruit borne of a year of my life, and it felt so viscerally wasted. Despair bought me honesty — by enrolling in graduate school, I’d made myself miserable for no reason. Why had I spent so much time in purposeless hard work? I arrived at a simple mechanism: an excessive sensitivity to the desires of others, and a competitive environment.

I ended up in physics through stubbornness, and an unusual willingness to suffer for the sake of grades. As an undergraduate, I was not particularly passionate about quarks, quasars, or quantum mechanics, but I was academically very competitive, and once I’d settled on physics as my major I determined to place myself at the top of my class. I did so by throwing myself into the hardest classes and putting in the hours required to ace the tests. This was, to put it mildly, a bad idea. I got a sort of grim pleasure from vanquishing my classmates in these academic slogs, but I was basically miserable. So why’d I keep it up?

Here’s the mimetic trap in short:

it hurts to leave, and there’s nowhere to go. It decouples the social reward signal from the rest of objective reality — you can spend years ascending ranks in a hierarchy without producing anything that the rest of humanity finds valuable. If you value the process itself, that’s fine. I didn’t. Cowardice kept me from acting on this, and after a while I came to believe I had to succeed in this field I’d fallen into essentially by chance.

So what can you do to escape this?

Don’t force yourself to do anything you hate. If you get too good at this, you won’t be able to figure out when to quit.

Enjoy the process of whatever you’re doing — you’ll be happier, and much more likely to practice, which leads to better outcomes.

Make sure your job has clear price signals for success and failure. Be suspicious of roles that compensate you with status or non-financial rewards.

Hold yourself to ambitious absolute standards in morals and productivity — write them down on post-it notes. You have an obligation to use yourself well, your time is valuable, and there are right and wrong ways to spend it.

Maintain a diversity of pursuits — you want to ensure that, no matter how engrossed you become in one, you never forget that the others exist.

Join Twitter — there’s no better way to reduce tunnel vision. Here’s a list of some of my favorite twitter follows.

Pair with: Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life

I liked this article by Fred Wilson on the merits of bringing back more face-to-face interactions. The debate of remote vs. in-person is still ongoing, with no signs of stopping.

We know that humans are better to each other in person. We know that in-person interaction is more meaningful, we are more present, and we connect in more fundamental ways.

So I believe that we must work in the coming years to get out of our offices (or homes) and see each other in person more often.

That means we should run fundraising processes that include meeting in person. We can do the initial screens (on both sides) over zoom, but the final selection process should include face-to-face meetings whenever possible. And board meetings should be done in person at least a few times a year. And those in-person meetings should include some social time in addition to business.

For companies, this means hiring should include a face-to-face meeting. Teams should meet in person regularly. Going to the office should be a regular occurrence for those that live near one.

It is time to get back to the office, at least some of the time. It will make for better business. And I also think it will make us happier at work.

Pair with: a16z Remote Survey

On the importance of creating rituals around your product:

Where this comes through in product isn’t so prescriptive — formats, features, even simple mechanics are fair game. Some examples below:

Limited supply. Content is abundant and attention is scarce. Habitual social apps serve as much as you’ll take, but limiting supply can help set up a ritual. Wordle single puzzle a day is refreshing. It feels low commitment and you get a sense of accomplishment from ‘completing’ a defined task. You also can’t binge and get bored or burn out.

Timed-release. Whether you want a user to create or consume, you can let them do it anytime or make consistent timing a core feature. Cappuccino collects ‘beans’ throughout the day but prompts you to listen the next morning; Dispo is similar but with photos revealed the next day.

Notifications. The ever powerful notifs, when used correctly and sparingly can be a great reminder and call to action. The more consistent and actionable the notif, the better. BeReal does this well (and it was core to HQ Trivia’s live game). Contrast this with habitual social where you get a slew of notifs based on a complex algorithm that’s ever-changing and opaque.

Give to get. In a give to get model, you have to create to be able to consume. BeReal makes you post before you can see your friends’ posts (Glassdoor is a great legacy example of the ‘give to get’ mechanic too). Why is this good? The canonical 90/9/1 rule of big social says 90% of users lurk, 9% contribute a little, and 1% a lot. Give to get means everyone contributes.

Streaks. Habitual social apps rely on extrinsic drivers (likes, views, follows) as incentives. But, the consistency underlying ritual apps can itself be gamified to create a sense of achievement and joy (either extrinsic or intrinsic value). Let users show their work publicly (e.g. Snap streaks) or celebrate their work privately (e.g. Wordle streaks, BeReal memories).

Graph structure. Social products are often defined by graph structure, i.e. open or closed, and, more colloquially, phrases like close friends, mutuals, groups, following, for you, etc. In multi-player formats, this tell us who directly impacts our experience. Single-player experiences can be indirectly social — through shared context or a collective experience (e.g. Wordle scores!). There isn’t a single right answer, but more intimate, participatory experiences or shared collective experiences lend well to a sense of ritual.

Pair with: The Revival of Consumer Social 📈

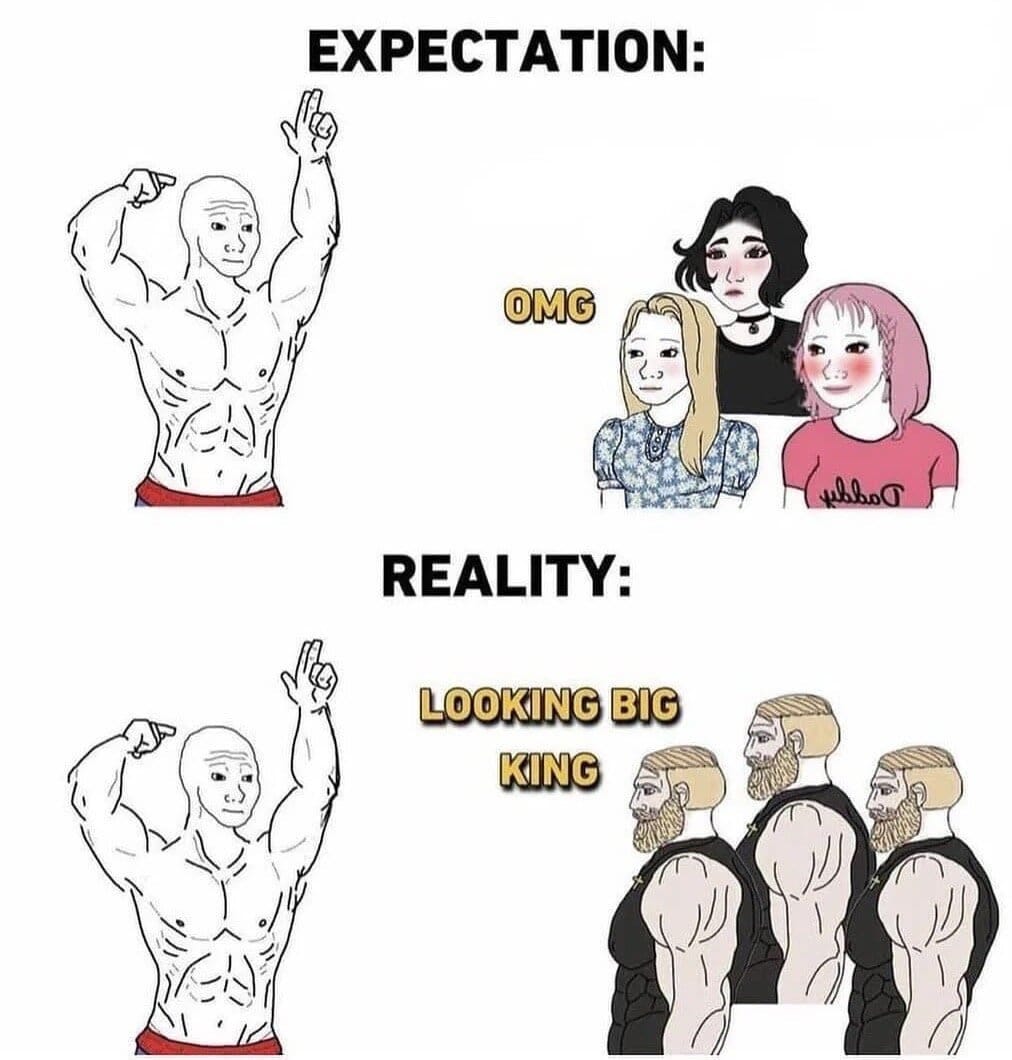

What intrasexual competition tells us about violence and male traits

“Male-typical traits such as beards and deep voices may be more about intimidating other men than they are about attracting women. In other words, these traits may be deers’ antlers rather than peacocks’ tails. To the extent that this is the case, the fact that women don’t always find them attractive is beside the point: That’s not why they evolved.”

This is a quote from the evolutionary psychologist Steve Stewart-Williams, in his excellent book The Ape That Understood The Universe.

The idea is that male secondary sex characteristics (beards, deep voices, large muscles) did not evolve primarily to attract women. Rather, the main reason men have them is to compete with other men.

Male-male competition is a fascinating and often overlooked aspect of human nature. The biologist Adam Hart has observed that when two males are in the early stages of conflict, they extend their arms out (“you got a problem bro?”).

The unconscious purpose is to increase the perception of body size.

The world is a very malleable place.

When I read biographies, early lives leap out the most. Leonardo da Vinci was a studio apprentice to Verrocchio at 14. Walt Disney took on a number of jobs, chiefly delivering papers, from 11 years old. Vladimir Nabokov published his first book (a collection of poems) at 16, while still in school. Andrew Carnegie finished schooling at 12, and was 13 when he began his second job as a telegraph office boy, where he convinced his superiors to teach him the telegraph machine itself. By 16 he was the family’s mainstay of income.

Readers (and often biographers) tend to fixate around the celebrity itself, when people became famous or fortunate. But the early lives, long before success, contain something revealing. Before you grasp, you have to reach. How did they learn to reach?

In my examples the individuals were all doing from a young age, as opposed to merely schooling. And while they may not have wanted to work, the work was nonetheless something that both they and society felt was useful: something purposeful and appreciated. In a sense they had useful childhoods.

Do children today have useful childhoods?

here’s my advice: read a book again and again and again, learning something new about it each time. read it five times before you open another one. pick a recipe you love and make it as often as possible, tweaking spices and techniques until it’s perfect and entirely yours. write it out on a notecard each time and put the final product in a rolodex. you can pass these on to your children! scan them for your friends! think of how lovelier that is than sending them a link to a paywalled nyt cooking article.

spend a month watching a great movie. watch the director’s cut and the behind-the-scenes documentary and then watch the films that influenced it and read the director’s favourite book. work to understand things, and not just the things themselves but the conditions that created them and the impact those things had on the world around them. let those things become a part of you instead of a distraction from yourself. i think the act of loving something should be generative and consuming — it should add something to who you are and lead you to a new understanding of all the parts that were already there. when i scroll on tiktok or whatever, i can’t get away from the feeling that almost nothing there is really meant to be loved — it’s just meant to be snorted, basically, and occasionally to get you to buy something.

i remember the feeling of teenage obsession, and i miss it desperately. few things about our everyday lives are more genuinely magical to me than the way that loving something with commitment can rewire your understanding of time: instead of dates or semesters, i can place moments of my early life inside the year where i only read vonnegut, the month i first loved the smiths, the autumn i spent with that rilke poem. it manages to make time physical — it turns it into something that can be tasted and touched. i want my life to be textured by the periods i spent perfecting a stone fruit hot honey cake or watching murder mysteries. wouldn’t it be wonderful to one day taste a cake and remember how you felt in september?

Peter Turchin’s Elite Overproduction Hypothesis is very interesting and particularly important to study right now.

Elite overproduction is a concept developed by Peter Turchin, which describes the condition of a society which is producing too many potential elite-members relative to its ability to absorb them into the power structure. This, he hypothesizes, is a cause for social instability, as those left out of power feel aggrieved by their relatively low socioeconomic status.

However, Turchin's model cannot foretell precisely how a crisis will unfold; it can only yield probabilities. Turchin likened this to the accumulation of deadwood in a forest over many years, paving the way for a cataclysmic forest fire later on. It is possible to predict a massive conflagration, Turchin argues, but not what causes it.

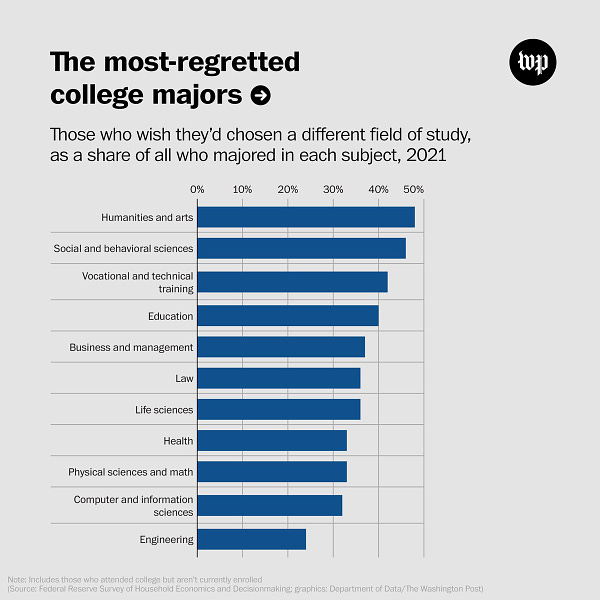

Elite overproduction has been cited as a root cause of political tension in the U.S., as so many well-educated Millennials are either unemployed, underemployed, or otherwise not achieving the high status they expect. Even then, the nation continued to produce excess PhD holders before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, especially in the humanities and social sciences, for which employment prospects were dim. Moreover, according to projections by the U.S. Census Bureau, the share of people in their 20s continued to grow till the end of the 2010s, meaning the youth bulge would likely not fade away before the 2020s. As such the gap between the supply and demand in the labor market would likely not fall before then, and falling or stagnant wages generate sociopolitical stress.

Noahpinion has a great piece on this concept and makes a case for this hypothesis.

A bunch of humanities careers vanished all at once

“If you graduated with a degree in English or History back in 2006, what would you do with that degree? If you wanted a secure stable prestigious high-paying job, you could go to law school and be a lawyer. If you wanted to live on the East Coast and work in an industry with a romantic reputation, you could work in media or publishing. If you just wanted intellectual stimulation and prestige, you could try for academia. If you just wanted security and stability and didn’t care that much about money or glamour, you could be a K-12 teacher, or work for the government.”

”But in the years after the Great Recession, every one of these career paths has become much more difficult.”

The revolution of rising expectations

“Why would this happen? If things get better for 20 years and then stop, why would you be mad? After all, at least things are better than they were 20 years ago, right?

But expectations matter. In the finance world, a number of economists have recently been playing around with the idea of “extrapolative expectations”. Basically, when a trend goes on long enough, people start to think there’s some sort of structural process underlying the trend, and therefore they assume the trend will continue indefinitely. For upwardly mobile people, or people in an economy that’s growing rapidly, or people whose stocks or houses are appreciating steadily in value, good times might come to seem normal.

And then what happens when it turns out that good times aren’t baked into the nature of the Universe? Suddenly, the mediocrity of reality intrudes upon the complacent expectations of eternal upward growth — housing prices plateau or fall, incomes hit a ceiling, economic growth stalls out. At this point, people could get quite angry.”

Unrest among the elite

“We like to think of revolutions as being carried out by downtrodden factory workers and farmers, and in some cases that’s true. But frustrated and underemployed elites are uniquely well-positioned to disrupt society. They have the talent, the connections, and the time to organize radical movements and promulgate radical ideas.”

The expectations reset

“Universities should avoid marketing materials that depict them as a golden ticket to wealth and intellectual fulfillment, and should offer career counseling that prepare students for a realistic job market. And government should implement apprenticeships, vocational education, free community college, and other programs that make working-class life a decent bet — in addition to reducing inequality, this will make college graduates feel less “elite” relative to their non-college peers.”

Pair with: The Revolt of The Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millenium (I haven’t read it yet, but it’s next up on my list!)

Alan has one of the best mindsets in Youtube Fitness.

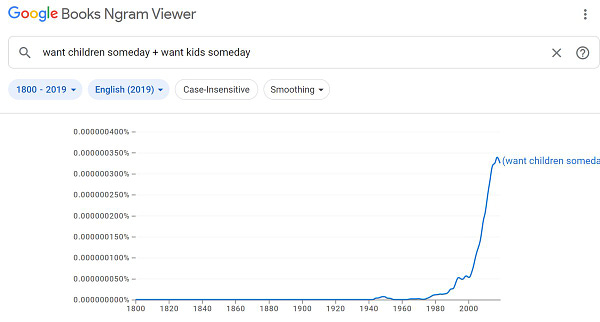

Based on Census Bureau historical data and Morgan Stanley forecasts, 45% of prime working age women (ages 25-44) will be single by 2030—the largest share in history—up from 41% in 2018.

I recently realized that not taking breakfast was no longer serving my goals. I restarted taking breakfast with protein powder and some nuts. I like this one, I’m not vegan, but it’s the powder I’ve had the most success with.

When you fight something, you’re tied to it forever. As long as you’re fighting it, you are giving it power. You’re giving it as much power as you are using to fight it.

— A. de Mello

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi