I’m back after taking a week off. It’s been a busy week, so I’m going to jump right into the newsletter.

The past few weeks have been incredibly painful for employees of media companies as numerous companies have announced layoffs and furloughs.

In the past week, it was revealed that The Economist, Vice and Quartz were all laying people off.

According to The New York Times:

Quartz’s owner, the Japanese financial intelligence firm Uzabase, announced the layoffs in a public filing Thursday. The company said about 40 percent of Quartz staff members would lose their jobs, with the cuts focused on the advertising department. Quartz had 188 employees at the end of last year, Uzabase said.

Zach Seward, the chief executive, said in a note to the staff that about 80 roles would be eliminated. A spokesman for the NewsGuild, the union representing 43 journalists working at Quartz, said on Thursday that about half its members would lose their jobs.

To explain the shift in business, Uzabase, the owner of Quartz, said in its quarterly results:

These factors have affected the advertising business of Quartz Media, Inc. (hereinafter referred to as “Quartz”), a US-based business media covering the global market acquired by Uzabase in July 2018. As such, Uzabase has decided to take the necessary steps to eliminate any potential future risks at an early stage, which will involve a shift towards a leaner structure through a fundamental business reform focused on restructuring the advertising business. At the same time, Quartz’s paid subscription business, launched after the acquisition by Uzabase, continues to demonstrate steady growth as planned, and Uzabase intends to maintain the focus on expanding it further

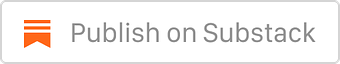

This is another example of ad revenue drying up considerably comparing Q1 2020 to Q1 2019. In the case of Quartz, it has dropped by more than half.

|

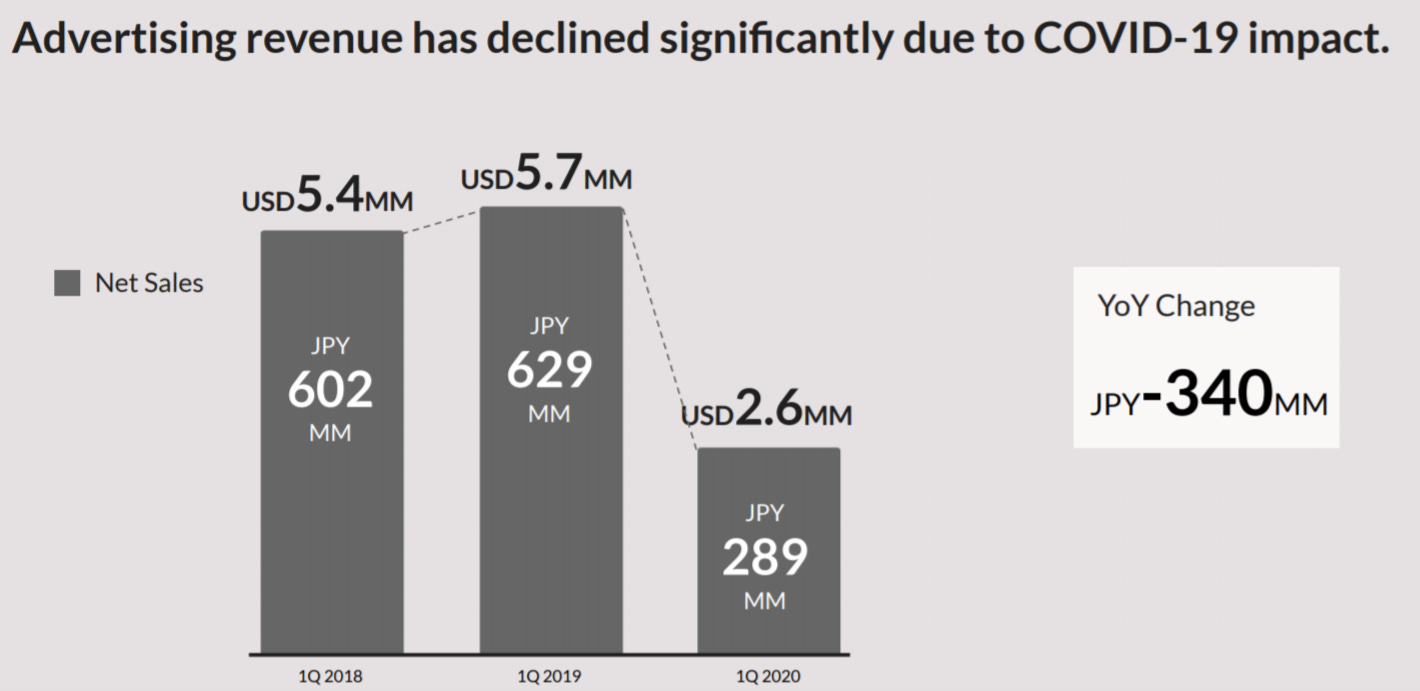

The rationale, according to Uzabase, is that the layoffs are necessary to make the business leaner and help it focus on its “growing” business of subscriptions.

The problem is that I don’t see the exciting growth that Uzabase says Quartz is having. According to the Q1 2020 Financial Results, Quartz saw a big jump in trial paid subscriptions.

|

Uzabase believes that Quartz will be profitable in 2021/2022; however, I do not see any path toward that. According to Uzabase, subscription MRR has grown to $118,000. To put that in context, it means that Quartz is earning approximately $1.4 million in subscription.

Yet, in Q1 alone, it lost $6.2 million. Those costs will obviously come down considerably because of the layoffs, but I’m still confused. Even if costs were to cut in half to $3.1 million per quarter, for the business to become predominately subscription revenue and profitable, it would need to grow MMR to a little over $1 million—that’s nearly 10x from where it is right now. Of course, the advertising business could return, which would help. But even then, Quartz has not been profitable for years, even when advertising was a larger percentage of the business.

I just don’t understand what Quartz is trying to do. It’s stuck in this weird middle ground where it’s trying to be everything for everyone, so it’s not focusing on any one audience. Let’s look at a few of its obsessions as examples.

One is called The Aging Effect, which is all about the new technology, services and care-giving concepts for an aging population. If that is my obsession, Quartz produced three pieces of content in April to serve me. Why would I pay for that? Instead, I can go to Aging Media and its network of sites. I’ll get way more bang for my buck.

Another example is called Space Business, which is pretty self explanatory. In April and May, Quartz has produced six pieces of content. SpaceNews.com produced a few pieces of content today alone. Again, why wouldn’t I go there?

Quartz is trying to manage a huge number of niches, but is offering no clear cut support for any of them. Effectively, it’s stuck in the middle, trying to compete with mainstream business publications; however, it’s not providing the same value that I can get there. Why pay Quartz $100 when $290 gets me all of Bloomberg News?

To make matters worse, it is cutting back on its editorial team in an attempt to save money. Most of the other publications we see expanding their subscription businesses are adding to the newsroom. I have a hard time seeing how Quartz is going to be able to tighten its budget while also growing a subscription business, especially when it is trying to be a bit of something for everyone.

Before I move away from the layoffs and the struggles of some of these publications, I wanted to touch on Vice. Axios reported last week that Vice was letting go 155 employees across the world.

According to the internal memo from CEO Nancy Dubuc that Axios obtained:

"Currently, our digital organization accounts for around 50% of our headcount costs, but only brings in about 21% of our revenue," Dubac wrote. "Looking at our business holistically, this imbalance needed to be addressed for the long-term health of our company."

That makes sense. However, what doesn’t make sense is what comes next:

Vice is moving as many individuals as possible over to its news division, where traffic has been exploding during the coronavirus crisis.

Why would anyone that is burning through cash choose to invest more money into the news division? Sure, traffic might be exploding, but it’s exploding across all sites since everyone wants to know what’s going on with coronavirus.

You know what’s not exploding? Ad revenue to news sites. Coronavirus is one of the most blocked keywords by advertisers. The more traffic that grows to coronavirus news, the weaker the ad revenue will be for Vice.

I said this back in March, but Vice is getting hit twice as hard because of its poorly structured deal with TPG and its over-reliance on ad revenue. I don’t believe these will be the last layoffs at Vice this year.

Should local be thinking more about data?

Will people pay for news? It’s a pretty tired question. However, it is integral to the topic of local news survival. While advertising might always play a part, the reality is, for local news to survive, it needs to get people paying.

One way I think we’re going to see local news start to push the conversion is with non-news products. More specifically, it’s going to be local products.

Take, for example, the Chicago COVID Resource Finder launched by CityBureau. Effectively, it is a database of over 1,300 resources filtered online in various languages with the ability to access it by SMS. The announcement piece describes the tool below.

That’s why, today, we’re introducing the Chicago COVID Resource Finder, a data bank of over 1,300 neighborhood, city, country and state resources that can be filtered so people can easily find what they need. Resources can be sorted by who is eligible (immigrants, families, business owners), what is offered (food, money, legal help), languages spoken and location. You can access it via SMS and by the end of the week the Resource Finder will be translated into 10 languages.

In this case, the product is free and I imagine that it would remain free because it is directly related to people’s safety. However, it’s an exceptional idea that only a local outlet could have created. A database of structured data that is specific to a local region is absolutely something people would pay for.

Jessica Lessin from The Information has written about this often. In a column back in April (paid), she wrote:

When Ashley founded her publication, she knew that journalism wasn’t the problem for outlets like hers. “The major lag for local news has always been the product,” she told me Friday as I checked in on how things were going.

Since the outbreak hit, she’s taken a number of clever steps to inform her community. For instance, she is using a Facebook group to debunk misinformation for local residents. She’s partnering with Outlier, a service people in Detroit can text to ask questions about the pandemic. Her team—15 part-time and full-time journalists—create charts on topics like the fact 5G does not cause the virus for Outlier to share.

In this case, what people are paying for is access to a product—the community of local residents having misinformation debunked. But the point Lessin makes is that publications need to be looking at offering data products as franchises that people might subscribe to. They come for the data and stick around for the news.

For example, let’s say there was a publication covering Dutchess County, NY (where I grew up). It’s got a population of 294,000. That’s not a terrible size for a local publication.

A reporter might report on the latest bill that the local politician is voting on. However, rather than writing an in-depth piece, this publication could build a database called “Dutchess Political Tracker” that tells me everything about what my elected officials specifically are doing. There are multiple towns and small cities in Dutchess, so each mayor would be covered too. Imagine how rich that could become.

That doesn’t mean there would be no reporting. Of course that’s to be expected and doing deep, investigative work remains an important part of the local reporter. However, if local news is meant to serve the community, providing updates on what’s happening in a structured data format versus long-form story might be a better experience for everyone.

The CityBureau example is a good one. It identified a data set that would benefit its users. Every local newspaper could do the same thing. Introduce a few of these and it’s possible you’ll have enough to justify a decently priced subscription.

Circling back on diversified commerce revenue

Before I wrap up, I wanted to circle back on something I wrote in April about Amazon cutting commissions. I said:

I never viewed the growth in commerce revenue as the saving grace for diversification as some publishers thought for two connected reasons.

First, diversification is about derisking your revenue profile. However, many publishers took the route of working with the largest player in town, earning large amounts of revenue from a single source. How does that derisk the profile?

Second, these affiliate links are just another form of advertising. Instead of charging on a CPM basis, you’re charging on a cost per acquisition basis. That’s still advertising.

There’s nothing wrong with that second point, of course. I’m a big fan of advertising. However, the real problem is that publishers have depended on the big players—Amazon, Walmart, etc.—to do the heavy lifting. With a single click, a publisher can gain access to a huge variety of products.

It’s probably common knowledge now, but for those that don’t know, there’s a new player out there that’s trying, ironically, to compete with Amazon on book sales. Called Bookshop, it’s offering publishers a 10% commission on all books sold.

According to Nieman Lab:

Convincing publishers to switch their affiliate links from Amazon to Bookshop became easier as sales increased and its conversion rate — which was 3 percent at launch — improved to a competitive 8 percent, Hunter said.

“That’s when it starts to become a really easy conversation because they don’t have to sacrifice revenue by linking to us,” Hunter said. “They get to feel good about themselves. They get to diversify the revenue. And they don’t have to take a financial hit because we’re able to deliver the sales that they want.”

That first paragraph is key. It’s easy to get excited about a 10% commission, but if the conversion is awful, the total revenue is weaker. Seeing Bookshop boost its conversion rate so successfully is encouraging.

In this case, it likely makes more sense to drive users to Bookshop than Amazon, especially if you’re covering books exclusively. It might not make as much sense if you find that people are buying a variety of other goods when they click your affiliate links. These are things you’ll have to analyze.

That about wraps it up! Thanks for reading today’s news round up. Please consider sharing this with your colleagues that would benefit from it. If you’re looking for even more A Media Operator, access to the comments and more conversations with me, become a paid subscriber. For paying subscribers, see you on Friday. Otherwise, see you next week!