Not Boring by Packy McCormick - Sc3nius

Welcome to the 854 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! Join 81,328 smart, curious folks by subscribing here: 🎧 To get this essay straight in your ears: listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… On the Tape If you like reading Not Boring, you'll love listening to On the Tape. Every Friday, CNBC Fast Money's Dan Nathan and Guy Adami, along with former hedge fund manager Danny Moses (of The Big Short fame) break down the biggest headlines impacting your money in the financial markets, demystifying the volatility in stocks, bonds, commodities, and of course, crypto. You'll leave with a nonconsensus perspective on financial markets and business news from three experienced voices whose goal is to provide listeners with the intellectual framework to think critically and make smarter investment decisions. In each episode, the co-hosts go Off The Tape with a guest from the world of finance, media, or sports. Recent guests have been former "Top Cop of Wall Street" Preet Bharara, NFL Star and financial literacy activist Ndamukong Suh, CNBC's Melissa Lee, Meltem Demirors and Raoul Pal on crypto, and Yours Truly. I'm about to make my third appearance 👀 To stay smart about your money, subscribe and tune in on every Friday. Hi friends 👋, Happy Monday! I hope everyone had a great weekend and has their Halloween costumes squared away. I am supposedly going to be Aladdin. I have 6 days to get in vest-no-shirt shape. I’m ngmi. In May 2020, a couple of months into the pandemic, I wrote my longest essay ever on a concept called scenius. Now, a year and a half later, we’re in the midst of a history-bending one. Let’s get to it. Sc3niusWe live in exceptionally rare times. We’re a part of the first global, internet-native Scenius. Throughout history, a handful of time-place combinations have punched so far above their weight in terms of contribution to human progress that their existence befuddled academics. In 1997, historian David Banks argued in “The Problem of Excess Genius” that, “The most important question we can ask of historians is ‘Why are some periods and places so astonishingly more productive than the rest?’" Figure out why, the logic goes, and we should be able to reproduce those productive periods and places on-command. But in his essay, Banks concluded that no one had sufficiently explained the phenomenon, in part because “essentially no scholarly effort had been directed towards it.” Twenty-three years later, Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison identified the same phenomenon in their 2020 essay, We Need a New Science of Progress:

They called for a new scholarly discipline, Progress Studies, which “would study the successful people, organizations, institutions, policies, and cultures that have arisen to date, and it would attempt to concoct policies and prescriptions that would help improve our ability to generate useful progress in the future.” The list of challenges facing humanity is long and complex: climate change, inequality, natural disasters, travel, education, and more. We can’t leave solving those hard problems to chance. Understanding those productive periods and places might give us insight into organizing ourselves in such a way as to maximize our chances of solving them. The same periods come up over and over again in these conversations because they were so head-scratchingly productive. Ancient Greece. Renaissance Florence. Elizabethan England. Northern England during the Industrial Revolution. Silicon Valley. These time-place combinations produce new ideas, new art, new economic structures, and new technology of astonishing breadth, quality, and staying power. Was it just random chance? Were an exceedingly large number of historical geniuses randomly born in the same small place in the same short timespan? Across the pond, British ambient musician Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno RDI (henceforth, “Brian Eno”) was scratching at the same question, focusing less on scholarship and more on vibes. He sought to push back on “the notion that gifted individuals turn up out of nowhere and light the way for all the rest of us dummies to follow.” In a letter to his friend Dave Stewart, published in his 1996 book A Year With Swollen Appendices, Eno wrote:

In the letter, Eno cited cultural examples like Dadaism in France, American experimental music in the late 50’s and 60’s, and punk in the 70’s, but also suggested that it would be “interesting to include scenes that were less specifically artistic - for instance, the history of the evolution of the internet.” Turns out, scenius shows up throughout history in those astonishingly productive places. It’s the best explanation I’ve seen for excess genius. According to Kevin Kelly, whose framework for scenius we’ll dive into shortly, “Scenius is like genius, only embedded in a scene rather than in genes.” To clear up some terms we’ll use here, “scenius” is the concept of communal genius, but we’ll use Scenius with a capital S to describe those magical time-place combinations. Scenius is the proper noun; scenius is the common one. Ancient Greece was a Scenius. The Renaissance was a Scenius. Silicon Valley was a Scenius. Historically, scenius had been tied to, and limited by, place. Early last year, pre-pandemic, I set out to write my longest essay to date on whether there could be an Internet Scenius that removed the physical boundaries and therefore unleashed more progress than any previous Scenius. There were about 100,000 people living in Florence during the Renaissance… if you multiply that by 79,000, do you get 79,000x the good ideas? Do you get even better ideas, thanks to more connections and better intellectual sparring? I started research for the essay in February 2020, and quickly became disavowed of the notion. There were three reasons I didn’t think we’d been able to conjure Scenius online:

Then, of course, COVID hit. COVID is the greatest catastrophe the world has experienced collectively since World War II, and it’s taken a terrible toll on human lives and the global economy. But I’m an optimist, and as I was writing Conjuring Scenius, I realized that it might also get us unstuck and create the conditions for an internet-scale scenius. Reading it back, a lot of the writing in the essay is cringey and overwrought, but I think I fucking nailed this prediction:

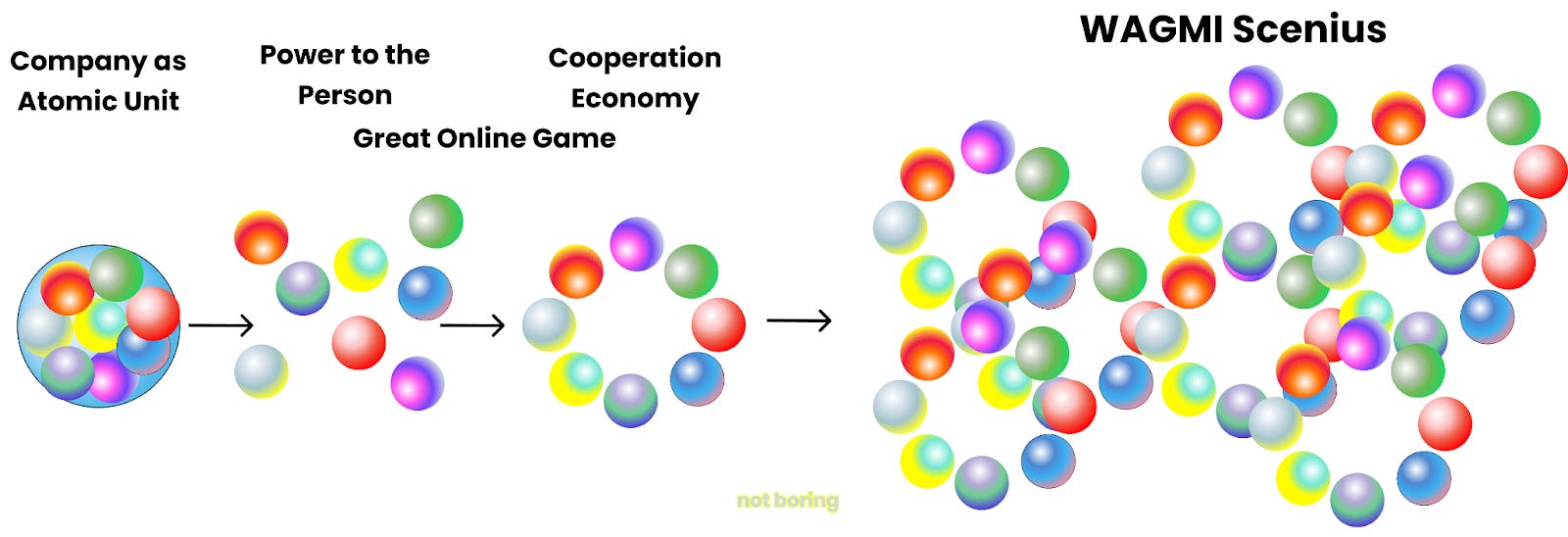

Seventeen months after I hit publish, we’re in the middle of a Holy Grail Scenius: global instead of local, with the internet as the scene, bound only by time but no longer by space. During COVID, we successfully moved large parts of the way we work and communicate online, unbound genius from geography, created new economic models and incentive structures, and made meaningful advances in healthcare, climate, finance, education, and more. This Scenius is also building the tools that will make other Scenia more common in the future. Part of the reason that we’re more productive now than ever before is just that we’re on an exponential curve, following the Law of Accelerating Returns, as I covered in Compounding Crazy. But I think it’s something bigger than that, a step change instead of a smooth curve. Since February, I’ve been writing an accidental series on how web3 is impacting culture, work, and the way that we all interact with each other. If Power to the Person was about how technology is empowering individuals as the new atomic units of commerce, The Great Online Game was about how the internet blurs the line between work and play for those individuals, and The Cooperation Economy was about how we play the game as teams of individuals or small groups, this essay goes one layer up to figure out how it all fits together: we’re all part of a great global Scenius. We’re all gonna make it. Let’s call it the WAGMI Scenius. I had a vague idea that web3 was at the core of a new Scenius when I started researching this piece, but what I didn’t appreciate is that web3 seems to be a toolkit for conjuring Scenius. More than financial speculation, web3 offers a set of tools that can align incentives in ways that allow groups to tap into their communal genius. We’ll focus mainly on web3 in this piece because it fits the Scenius framework so beautifully, but the WAGMI Scenius isn’t limited to web3. The conditions are ripe for progress, and the culture is coalescing around the same ethos that has defined Scenia of the past, but this time, the whole globe is participating. The outputs are unpredictable, but when all is said and done, I still believe historians will look back at this period as the most productive and creative in human history to date. Plus, the models we develop today might play a critical role in shaping how we govern our new frontiers: space and the Metaverse. This essay is an attempt to put … gestures broadly at everything … into historical context and guess at where it’s headed. To understand what’s going on, why, how, and how to contribute, we’ll cover:

Scenius is a vibe -- one of those, “you know it when you see it” things -- but there’s also a framework of exogenous and endogenous factors that nurture scenius and help us identify it. Deconstructing SceniusThere are two sets of factors that make for a productive Scenius:

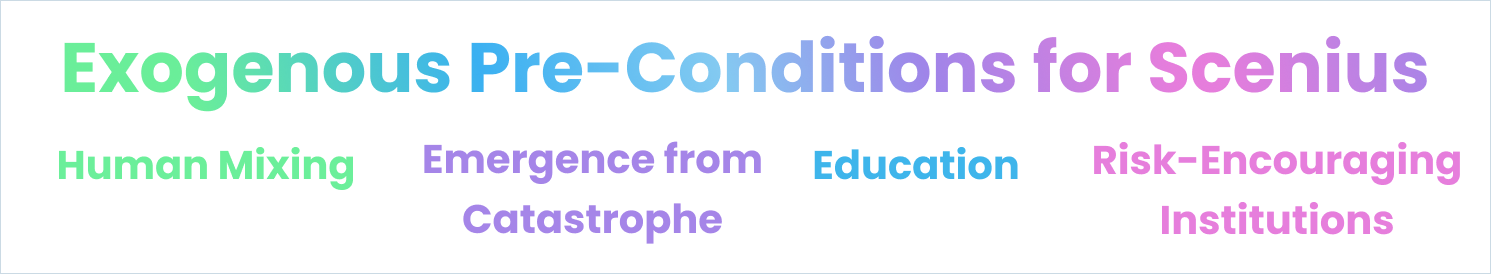

The first part is luck -- whether the environment is right for Scenius at a given time -- and the second part is what the people in the scene do with that luck to make the most of the opportunity. Let’s start with the Exogenous. Exogenous Factors David Banks ended The Problem of Excess Genius with disappointment that so little, well, progress, had been made in understanding why intellectual hot spots appear on the map when and where they do. Finally, fifteen years later, in a 2012 Wired article, Cultivating Genius, author Johah Lehrer proposed an answer to Banks’ question, citing Nobel Laureate Paul Romer’s work on meta-ideas, or ideas that support the spread of other ideas. He suggests three that have been present in eras of excess genius, like Renaissance Florence and Elizabethan England:

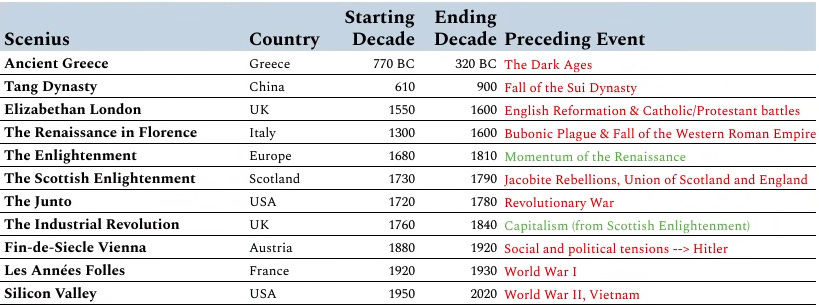

In Conjuring Scenius, I tried to add some ingredients to the pot, and one in particular seemed to appear before most of history’s great Scenia: catastrophe. Take a look: Ancient Greece followed the Greek Dark Ages, a 350 year period after the collapse of the Bronze Age. You can draw a direct line from World War II to Building 20 at MIT, Bell Labs, and ultimately, Silicon Valley. The Junto came out of the Revolutionary War. The Renaissance emerged from the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Bubonic Plague. The two above that didn’t emerge from catastrophe rode the momentum from a previous Scenius and used its outputs as building blocks. Why does Scenius emerge from catastrophe? For one, catastrophe focuses energy, attention, and talent. The US Government pulled the brightest minds in the nation together to develop new technology to power the war effort, and those technologies, like the transistors that came out of Bell Labs, formed the foundation of Silicon Valley. Second, crisis shakes and breaks and calls for new solutions. When everything is burnt to the ground, there’s room for new ideas and institutions to grow. Ben Franklin’s Junto created the first volunteer fire company, public library, and philosophical society in the young United States of America, along with the University of Pennsylvania. Third, catastrophe brings people together in ways that are difficult to accomplish in peacetime. In Tribe, Sebastian Junger wrote:

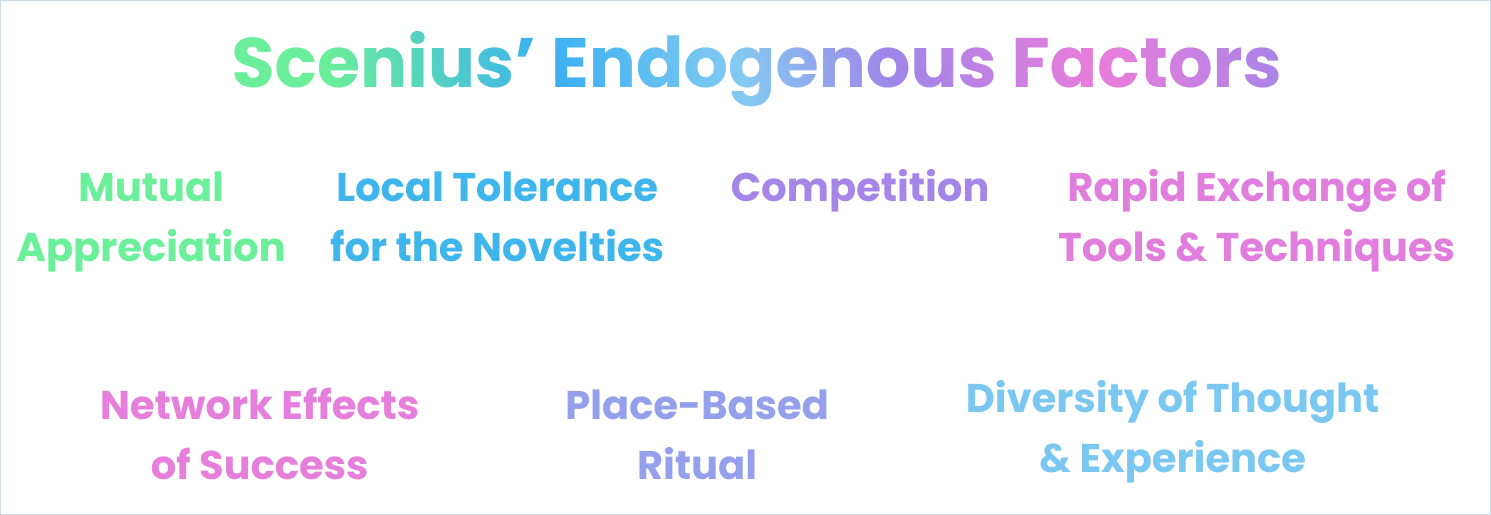

Even after the catastrophe ends, there seems to be an afterglow, during which newly-formed channels of collaboration continue to bear fruit. Those four factors -- human mixing, new educational models, institutions that encourage risk-taking, and catastrophe -- set the stage for Scenius. Then the endogenous factors take over, and it’s up to the scene to make its impact. Endogenous Factors A little over a decade after Brian Eno named and defined scenius, Wired’s Kevin Kelly popularized the term in the tech community and put a framework around it. In a 2008 blog post, Scenius, or Communal Genius, Kelly looked at some historical examples and came up with four factors that nurture scenius once it takes root:

Kelly’s four factors are present in any scenius, from the purely artistic to something as local and specific as Yosemite Park’s Camp 4. In Conjuring Scenius, I added four ingredients that seem to be present in all of the examples of the great Scenia that had a lasting impact on the world. One was emergence from catastrophe, described above, and the remaining three are endogenous factors that can be used to strengthen the Scenius:

Those eleven factors -- four exogenous and seven endogenous -- can turn groups of individuals into a Scenius, a community that accomplishes much more, across a range of disciplines, than would otherwise be expected from a group of people with the same talents. There have certainly been groupings of people as intelligent as those alive in Ancient Greece or Florence during the Renaissance who lived in the same place around the same time; without the right underlying conditions, however, they weren’t able to combine their talents in any way meaningful enough that we remember and build upon their contributions today. When they are in place, though, magic happens. And they’re in place right now. To see how that framework fits the WAGMI Scenius and where this is all headed…How did you like this week’s Not Boring? Your feedback helps me make this great. Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad Thanks for reading and see you on Thursday, Packy If you liked this post from Not Boring by Packy McCormick, why not share it? |

Older messages

Playing Solo Games

Monday, October 18, 2021

Not Boring Capital: Fund I, Update II

The Model of Everything

Thursday, October 14, 2021

Not Boring Investment Memo on ScienceIO

Log in to Not Boring by Packy McCormick

Tuesday, October 5, 2021

Click here to log in

Log in to Not Boring by Packy McCormick

Tuesday, October 5, 2021

Click here to log in

Log in to Not Boring by Packy McCormick

Tuesday, October 5, 2021

Click here to log in

You Might Also Like

🔮 $320B investments by Meta, Amazon, & Google!

Friday, February 14, 2025

🧠 AI is exploding already!

✍🏼 Why founders are using Playbookz

Friday, February 14, 2025

Busy founders are using Playbookz build ultra profitable personal brands

Is AI going to help or hurt your SEO?

Friday, February 14, 2025

Everyone is talking about how AI is changing SEO, but what you should be asking is how you can change your SEO game with AI. Join me and my team on Tuesday, February 18, for a live webinar where we

Our marketing playbook revealed

Friday, February 14, 2025

Today's Guide to the Marketing Jungle from Social Media Examiner... Presented by social-media-marketing-world-logo It's National Cribbage Day, Reader... Don't get skunked! In today's

Connect one-on-one with programmatic marketing leaders

Friday, February 14, 2025

Enhanced networking at Digiday events

Outsmart Your SaaS Competitors with These SEO Strategies 🚀

Friday, February 14, 2025

SEO Tip #76

Temu and Shein's Dominance Is Over [Roundup]

Friday, February 14, 2025

Hey Reader, Is the removal of the de minimis threshold a win for e-commerce sellers? With Chinese marketplaces like Shein and Temu taking advantage of this threshold, does the removal mean consumers

"Agencies are dying."

Friday, February 14, 2025

What this means for your agency and how to navigate the shift ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Is GEO replacing SEO?

Friday, February 14, 2025

Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) is here, and Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is under threat. But what is GEO? What does it involve? And what is in store for businesses that rely on SEO to drive

🌁#87: Why DeepResearch Should Be Your New Hire

Friday, February 14, 2025

– this new agent from OpenAI is mind blowing and – I can't believe I say that – worth $200/month